Since your humble diarist took some time off, today’s Sullivan diary entries come from two days, back-to-back:

28 September, 1891

Went to city – called on Sir J. Pender about Bertie.

29 September, 1891

Went to Newmarket (1st Oct: Meeting) to stay

with Russie. wrote to Valabrègue etc. Bertie accompt

me to station & went to see Sir John Pender afterwards.

Today, Sullivan is taking the train to Newmarket because, of course he is. He almost never misses the horse races at Newmarket, which often makes his diary entries for this time of year rather dull. Tomorrow’s entry is just “Newmarket”. Russie is his old friend and betting buddy Russell Walker, about whom I write a few lines here. Valabrègue is probably the poet Antony Valabrègue, but that’s a story for another day. Bertie is of course Sullivan’s nephew Herbert, who is 23 years old at this time.

The story for today involves Sir John Pender. His name does not appear in Arthur Jacob’s Sullivan biography, but it may appear—in what would be quite a coincidence—in a footnote to Michael Ainger’s Gilbert and Sullivan: A Dual Biography. In footnote 18 of chapter 9, Ainger references a letter from W.S. Gilbert to “J. Pender.” Dixon’s index of Sullivan’s diaries lists him as Pender(?). So whoever is he, he isn’t well known to Sullivan scholars, and probably wasn’t even an acquaintance of Sullivan, before now.

A quick search reveals him: Sir John Pender, (10 September 1816 – 7 July 1896), “a Scottish submarine communications cable pioneer.” That’s an understatement. Go read his bio, he was the driving entrepreneurial force behind submarine cable laying in the nineteenth century.

So why did Sullivan meet him? And then why did Bertie meet him the next day? In truth, I don’t know for sure, but I can think of one reason: Sullivan was trying to get a job for Bertie.

What did Herbert T. Sullivan study?

First, some background. Herbert was the son of Sullivan’s brother Fred, who passed away at the age of 40 in 1877, when “Bertie” was 9. Bertie was the oldest boy in a brood of eight children. According to a letter from Sullivan to his mother in 1877, we know that Bertie was sent down to Brighton, to a boarding school. So far as I know, Sullivan does not identify the school, but it might have been Brighton College. I’ll give the source of that hypothesis in a moment. I have asked the college for comment.

Herbert’s mother Charlotte remarried and in 1883 relocated her family to Los Angeles, but 15 year old Bertie stayed in England to live with his Uncle Arthur. The next year, Sullivan took the lad to Zurich, “where the intention was to enroll him in the Polytechnikum for training as an engineer,” according to Arthur Jacobs. Jacobs does not cite a source for this “intention,” but to be fair, he wasn’t writing a biography of Herbert Sullivan.

His hypothesis probably came from Sullivan’s diary, but his conclusion hides quite a bit of interesting story. The Polytechnikum of Zurich is a college today called ETH Zurich. In 1884 it was, as it is now, a very well-respected center of science and engineering, one of the leading institutes of Europe. The entrance requirements of the Polytechnikum were strict and exclusive. In fact many readers who are familiar with the history of science must already be grinning at this point of my tale.

Let’s allow Sullivan’s diary to take over, and I will add some annotations as we go.

8 November, 1884

Left Paris 8.25 […] arr Mulhouse

6.18. Alfred v Glehn met us at the

station. Put up at Hotel Central, &

supped at Alfred’s, who is married.

He praised the Polytechnical School

at Zurich highly.

I have no doubt that Alfred praised the Polytechnikum! But who is Alfred v Glehn? Alfred is the son of Robert William von Glehn (1801-1885). His surname “von Glehn” is confusing, as he was reportedly born in a part of Russia which is now Estonia, but his family came from Glehn, which is a German town near Cologne. At some point in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century, most of his descendants changed their family name to “de Glehn,” to sound less German. But at this time, Sullivan usually refers to them as “v Glehn.”

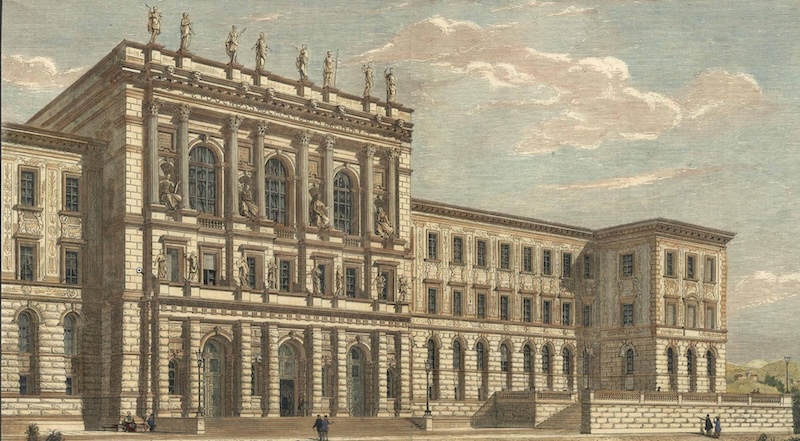

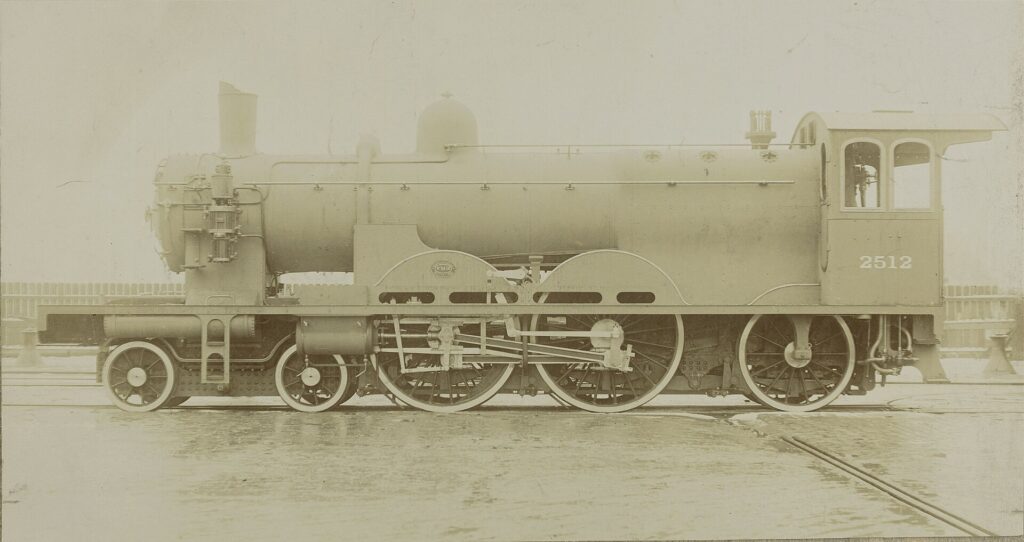

Students of Sullivan’s early career will know that Robert von Glehn moved to England and married a Scottish lady called Agnes Duncan. He did very well for himself financially, they had 12 children, and he installed his English family at an estate called Peak Hill Lodge. The Lodge was located in the London suburb of Sydenham, a town which was the home of the Crystal Palace, the scene of England’s first performance of Sullivan’s music, and still at this time a center of serious English music. The von Glehn’s were fans of art and music, and their home was a frequent haunt of Sullivan friends George Grove, Frederick Clay, John Millais, and Francis Burnand. Among Robert’s children was Alfred, who was particularly brilliant. He studied at King’s College London, and later at … you guessed it … the Polytechnikum of Zurich. By this time, 1884, Alfred had relocated to Mulhouse in France to work with the Société alsacienne de constructions mécaniques where he revolutionized the design of railway locomotives.

Born in 1848, Alfred Von Glehn was close to Sullivan’s age, so it is reasonable to assume they had become friends back in the 1870’s. It is also possible that Sullivan, himself having had only a lower middle class boarding school education, had few other friends with such impressive scientific credentials. It is also likely that Sullivan was acquainted with Alfred’s older brother Alexander. Alexander had a son called Wilfred, who was just two years younger than Sullivan’s nephew Herbert. Alexander sent his boy to Brighton College.

So, in 1884, having brought 16-year-old Bertie to meet his old, brilliant friend Alfred von Glehn, the next day …

9 November, 1884

Left Mulhouse. 9.10. arr: Zurich

[…] Called at once on Prof: & Mad. Ganter – very nice

people. discussed the matter of Bertie’s

education, & decided to take him to

Germany first, to learn the language. Spent

the evening with them.

We’re in Zurich, and this, I imagine, is how and where Arthur Jacobs developed the idea that Sullivan’s plan was to enroll Bertie in the Polytechnikum. “Professor Ganter” was a mathematician called Heinrich Ganter. But as it happens, Ganter isn’t exactly on the faculty of the Polytechnikum. I’m taking his history from a book by Lewis Pyenson of Western Michigan University. I’ll mention his book’s title in a bit, because I’m really enjoying stretching out the amazing reveal in this story.

Pyenson writes of Heinrich Ganter:

He chose teaching. By 1877 Ganter found himself an instructor at the Realgymnasium in Karlsruhe. His advancement limited by an incomplete education, thirty-year-old Ganter decided to return to school. He spent three years studying mathematics at the universities of Berlin and Zurich. While a student at Zurich he worked as an assistant for higher mathematics at the Polytechnic and at the local Gymnasium. He received a doctorate from Zurich in 1884. Two years later he arrived at Aarau.

So it appears that about the time Sullivan and Herbert come to call on him, Dr. Ganter has just received his Polytechnikum doctorate. It also appears that it is Ganter who informs Sullivan that Bertie’s lack of German means he isn’t going to make it as a Polytechnikum man. That takes us to the next day …

10 November, 1884

Left Zurich. 9.30. Took Bertie to Freiburg

(Breisgau) arrived: 4 p.m. took him to the

house of Mr. Tritscheller, 9 Erbprinzen

Strasse, whose wife is Prof: Ganter’s sister.

I left him there (£90 a year) paying 1st

quarter in advance – & returned by 6.2 train

to [Basel] – slept at Hotel Euler.

Heinrich Ganter has referred Sullivan to his sister, now a Mrs. Tritscheller, who lives in Freiburg im Breisgau. Sullivan has brought Bertie there and … left him there.

For me, the hilarious part of that diary entry, is that Sullivan then traveled alone to Basel and slept at the “Hotel Euler.” Because here’s the fun part of this story.

If Herr Ganter believed that Herbert Sullivan was not yet ready for entrance into the Polytechnikum, this would not be the last time he gave a young hopeful advice in that area. As Mr. Pyenson noted above, Ganter moved to the town of Aarau, about 35 miles from Zurich. In 1895, Ganter will teach mathematics to a young man who had failed the Polytechnikum‘s rigid entrance exams.

The title of Lewis Pyenson’s book is Young Einstein.

All of this is backstory to the question of why Bertie should meet Sir John Pender in 1891. I’ll continue the story in Part 2.