7 November, 1899

Bendall took printer’s copy of “Ab: Mind: Beg:” to Balch –

Daily Mail – also my M.S. to Alhambra for Byng to score.

Rehearsal at Savoy.

It’s a busy time for Sir Arthur Sullivan. It’s been more than three years since the production of The Grand Duke, his final collaboration with W.S. Gilbert. Since then, Sullivan has managed to produce only two large works, the ballet Victoria and Merrie England, and the comic, but rather unfunny, opera The Beauty Stone. The latter became Sullivan’s worst theatrical failure, being cancelled after only 50 days in the theatre.

Following the failure of The Beauty Stone, and then a probable threat of public humiliation via bankruptcy in 1898, Sullivan resolved to give up, for the following years, all plans of producing serious works and devote all efforts to making money. He spent some months in discussions with successful writers of musical comedy, in search of a new writing partner. The search led him to Captain Basil Hood, who may be mentioned in Sherlock Holmes, and with whom Sullivan first discussed collaboration almost exactly one year ago. Now, after some delays, they are rehearsing their first opera, The Rose of Persia, at the Savoy Theatre.

The work has been going well. Sullivan began composition in July. Except for occasional days of travel or betting on horse races, he has maintained an admirable, steady work schedule. Unlike his experience with The Beauty Stone, which included much frustration with the authors (particularly Arthur Pinero), Sullivan’s diaries record almost no friction between himself and Captain Hood. Instead, both Sullivan and Helen Carte have left us remarks about what a kind and pleasant gentleman was the retired officer.

Nonetheless the delays are expensive for Sullivan. Although Victoria and Merrie England earned him £2,000 plus a percentage of sales in 1897, that sum was not enough for Sullivan to maintain the payments on at least three large loans. Since The Beauty Stone earned him essentially nothing, Sullivan’s incomes were reduced to royalties on publications, royalties on revivals and tours of his previous operas (H.M.S. Pinafore is currently playing at The Savoy), and possibly some dividends on his stock holdings. Unfortunately for those latter earnings, much of Sullivan’s portfolio was held by banks in collateral for his loans.

Sullivan’s situation was summarized in 1927 by his biographer Cunningham Bridgeman. In the book Gilbert, Sullivan, and D’Oyly Carte, by François Cellier and Bridgemam, Bridgeman gives us one of the few public glimpses of Sullivan’s financial position we have from a contemporary eyewitness:

An incident associated with the production of this opera [The Rose of Persia] recurs to my mind. One day I happened to meet Sullivan coming from rehearsal. He was looking worn and worried. I anxiously inquired the cause of his dejection. “My dear fellow,” he replied, “how would you feel if, whilst you were in the throes of rehearsing an opera, you were called upon to set ‘The Absent-minded Beggar’ for charity? That’s my trouble! All day long my thoughts, and at night my dreams, are haunted by the vision of a host of demon creditors pursuing me with the cry, ‘Pay—Pay—Pay’!

That anecdote continues with a remark that Sullivan found the text of the song difficult to set to music. I will address that story in a later post.

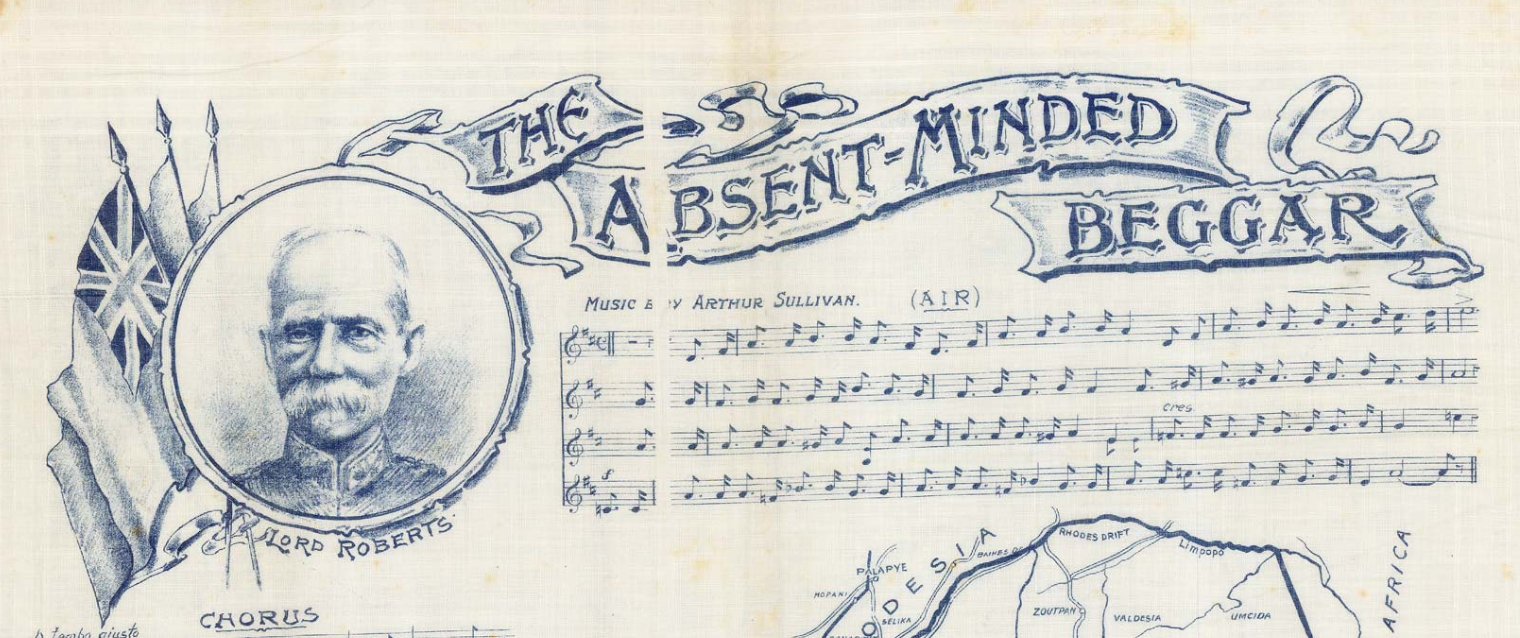

So what was The Absent-minded Beggar?

It was a poem written by Rudyard Kipling, father of Baloo the Bear. The poem was designed to inspire patriotic British to donate money to the families of British soldiers being mobilized for the Boer War.

Ok, what was the Boer War?

I’m no expert on that conflict, which lasted from October 1899 to May 1902, so of course I’m going to summarize it for you (experts, please give me your opinions of my summary!). The so-called Boers (farmers) were the successors of the Dutch imperialists who conquered a part of what is now South Africa, then known as The Transvaal. In 1886, gold was discovered there. The Transvaal Republic bordered some territories which had been invaded by Britain. After the gold discovery, the British were anxious to obtain mining and citizenship rights in the Transvaal. The period from 1886-1899 saw a gold rush during which many British mining syndicates were formed, stocks were floated, and mines were dug. Some Brits became very rich. By 1899 there was so much British wealth tied up in South African mining stocks (of various qualities) that a British takeover of the Transvaal became inevitable.

As I said, I’m no expert here, so take that summary as my own simplified, opinionated narrative. By the way, one of the thousands of British investors in South African gold mining shares was Sir Arthur Sullivan. At his death a year later, he held shares in several South African mining and land companies. They didn’t make him rich.

However accurate or otherwise be my summary above, the Transvaal knew what was up and attacked the British colonies in October. Being caught somewhat flat-footed, Britain began what would become an immense mobilization of forces. Suddenly, British families whose military pay—often augmented by civilian work—kept them fairly secure at home, were faced with losing their breadwinners and having their pay reduced to low combat wages. Charities were formed to somehow ameliorate their plight. Fundraising for these charities was supported by nationalist newspapers (known as the jingoists from a song of 1877: We don’t want to fight but by Jingo if we do…) who used the charitable appeals to buttress pro-war propaganda.

Readers of today’s newspapers in the UK will perhaps not be surprised to discover The Daily Mail among these publishers, and neither perhaps Rudyard Kipling as the poet. Kipling wrote the poem in mid October and sent it to The Daily Mail with a sort-of shareware pitch. He didn’t want to receive any money for the work, and would not hold any copyrights thereto. Instead, he wanted the poem to be freely printed, published, and read everywhere, assuming the printers and performers honorably donated all the proceeds to the cause.

At least that is one version of the story. A more likely version, supported by Kipling’s later writings, is that the charity drive was a “stunt” (Kipling’s word) invented at the Mail, who then pitched the idea to Kipling. Today the Mail’s claim is that they commissioned Kipling. Whichever version happened, public response to the poem was immediate and positive. Readings of the poem began at music halls. Copies in various forms were printed and sold at inflated prices. At some point before 1 November, someone approached Sullivan about setting the poem to music. Sullivan’s diary does not explicitly name that person. But on 1 November, Sullivan wrote:

1 November, 1899

Bendall went to see Balch, editor of “Daily Mail” about

my setting Kipling’s “Absent minded beggar” to music.

Which rather supports the idea of The Daily Mail having engineered the whole affair. Bendall is of course Wilfred Bendall, Sullivan’s secretary. Balch is William Ralston Balch, an American journalist working at the Mail. By an odd coincidence (?), Balch had previously published a “ponderous volume” (said a contemporary review) entitled The Mines, Miners, and Mining Interests of The United States in 1882, in which I’m quite sure he later regretted including the sentence “The riches in gold of the African continent is a thing of the past.” I am constantly amazed by how many people mentioned in Sullivan’s diaries are connected to mining.

The above diary entries contain almost everything Sullivan has to say about setting The Absent Minded Beggar to music. He might have worked on it on 3 November, and on 5 November he notes finishing it. Finishing, here, meant just the song, probably with a piano accompaniment. Sullivan left the orchestration work to George W. Byng. Byng was the house composer of the Alhambra Theatre, where The Absent Minded Beggar will be given its first public performance on 13 November.

I hope you’ll join me for that spectacular event in Part 2.

[…] second meeting concerns The Absent Minded Beggar. As we saw in Part 1 of this series, Sullivan has agreed to set the poem by Rudyard Kipling to music, for a charity scheme invented by […]