22 September, 1885

Went to Rockaway races with Mrs R & Adele.

got into the wrong train returning, went to Brooklyn

over the Bridge & by “L” Railway home. & dined at Dels

at 8.30! Beastly wet day.

It’s 1885 and Sullivan is in New York City, five days away from facing a scandal in the press (see Part 1). A newspaper owned by Alfred Pulitzer has run the story that Sullivan is wooing Geraldine Ulmar, his new soprano, and will propose marriage soon. Worse, it is his mistress Fanny Ronalds who first shows him the paragraph. Sullivan is furious, but he has been paying Miss Ulmar a certain amount of attention in recent weeks.

In his diary on 27 September, Sullivan writes “that scoundrel Byrne wrote the paragraph principally”. Today’s entry sounds like a more fun day for Sullivan, and involves a young lady whom the rumor mills will also link with Sullivan. But first, who is “that scoundrel Byrne”?

Sullivan doesn’t tell us, but I believe it was almost certainly Charles Alfred Byrne. If so, this story also links Sullivan (distantly) with an American electoral scandal.

Charles Alfred Byrne, or “C. A.”, was a writer, dramatic critic, and lyricist, who tried his hand at several entrepreneurial ventures. In 1880 he published a newspaper called Truth. 1880 was a US presidential election year, and a key campaign theme, for all parties, was hating Chinese immigrants. Two years later Congress would pass The Chinese Exclusion Act. It was not a good time for a presidential candidate to be pro-Chinese.

The Republican candidate for president was James A. Garfield, a congressman from Ohio. According to the James A. Garfield National Historic Site, on 20 October, 1880, two weeks before the election:

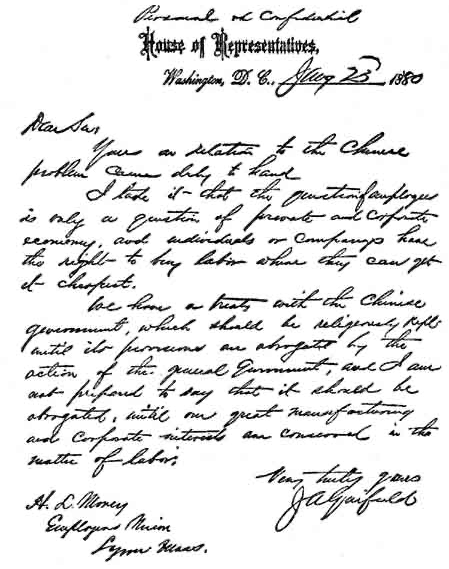

Garfield received a telegram that day asking about a letter the congressman had supposedly written on “the Chinese question.” Within hours he was sent the text of the letter. Written on House of Representatives stationery and dated January 23, 1880, it was addressed to an H. L. Morey of the Employers Union in Lynn, Massachusetts. In the letter, Garfield allegedly said that “individuals and companys [sic] have the right to buy labor where they can get it cheapest.” Further, the letter says that the treaty with China should remain in effect “until our great manufacturing and corporate interests are conserved in the matter of labor.” Garfield immediately denied that he had written it.

Charles Byrne’s Truth published the letter the next day, saying that a friend of the Republican candidate—a prominent Democrat—had confirmed that the handwriting was Garfield’s. A furious political scandal ensued. Garfield released a hand-written letter of denial to the press, who ran it side-by-side with the Morey Letter, to show that the latter was a bad forgery. It was soon reported that the person to whom the letter was addressed did not exist, nor did his organization.

But in 1880, news took several days to propagate from the east coast to the west. Garfield lost California by 94 votes, but won the election overall. He was assassinated a few months later.

Where did Byrne get the letter? Byrne and Truth journalist Kenward Philp were put on trial for libel and forgery, but were acquitted. Historians today say we don’t know.

Sullivan most probably knew Byrne as the editor of another one of his startup newspapers, The Dramatic Times. I haven’t found a connection between that paper and Pulitzer’s Morning Journal, but Sullivan was not the only person who accused Byrne of libel.

Back to 22 September, 1885

Sullivan spends a day at a horse race—not at all an unusual occurrence in his life—with two beautiful ladies, his mistress Fanny Ronalds, and Adele Grant, the 19-year-old daughter of David Beach Grant, of the prominent banking and locomotive-building family. Sullivan has known Adele since she was a young girl; now she’s a beauty, frequently mentioned in the society press. Sullivan has spent a lot of time with Adele and her family during his stay in New York, which also leads to some press attention. For the details of Sullivan’s attentions to Miss Grant, I recommend J. Donald Smith’s account in Magazines 91 and 92 of the Sir Arthur Sullivan Society.

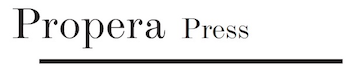

The Rockaway race was a steeplechase organized in Far Rockaway, New York. The Rockaway Steeplechase Association has recently built an impressive new course and club house, and today in 1885 are initiating yearly races. Betting is allowed.

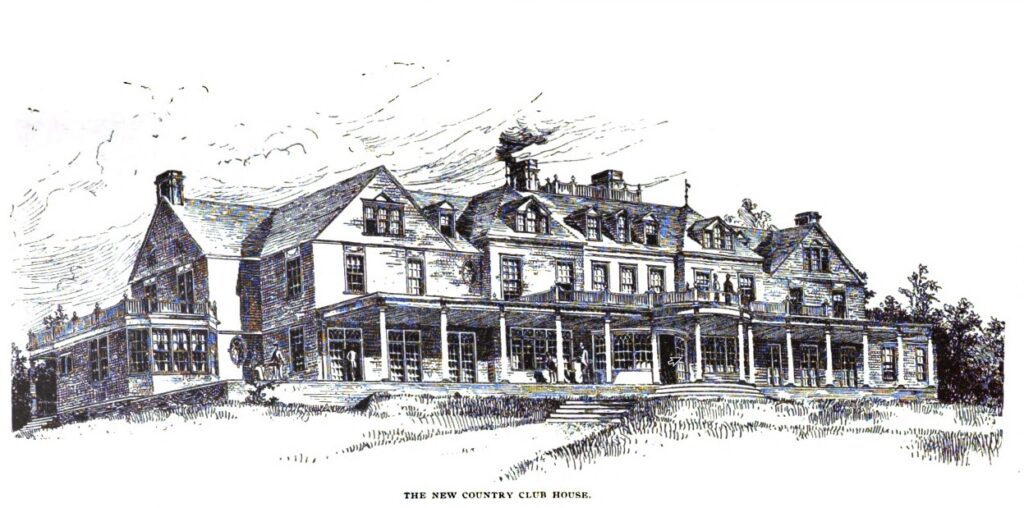

On his way back to Manhattan, Sullivan takes the wrong train and ends up in Brooklyn. To correct the problem he takes an “L” train, probably the Brooklyn Elevated Railway or “L” for elevated. By amusing coincidence, this route is today handled by the “L” subway line. At this time, the Brooklyn Bridge is barely two years new. There was a toll for crossing it.

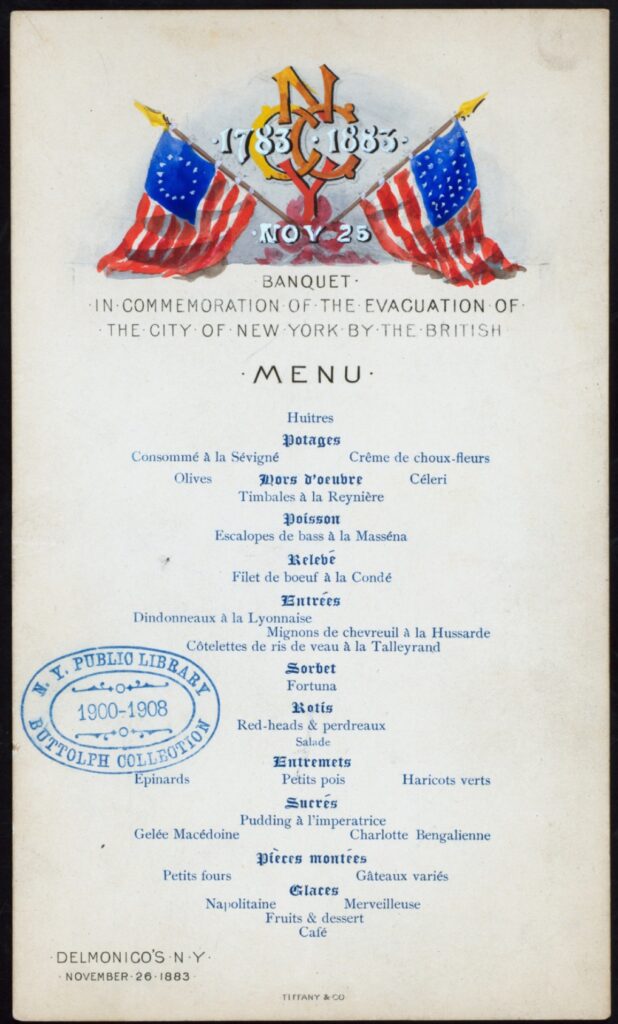

Lastly, he dines at Dels, which is the famous Delmonico’s Restaurant. When he travels, Sullivan seeks out the best, most exclusive restaurants, and he tends to patronize them many times. Delmonico’s is his go-to place in New York. Its menu is exclusively in French.