23 September, 1888

Began sketching Overture – Mrs R. & Reggie arrived

at Euston 6.45 tired, all dined here at 9.

It is 1888 and Sir Arthur Sullivan is about to complete his finest work of comic opera, The Yeomen of the Guard. This is obviously my opinion. But today he’s working on one of the finest pieces of his career, and I think many people agree with me.

As is his usual procedure, Sullivan has left the composition of the opera’s Overture until last. You probably know that for some of the earlier operas, he didn’t write an overture but handed that task off to someone else. At this date, he hasn’t written an overture since 1884’s Princess Ida. Starting today, in future he will write all his own overtures.

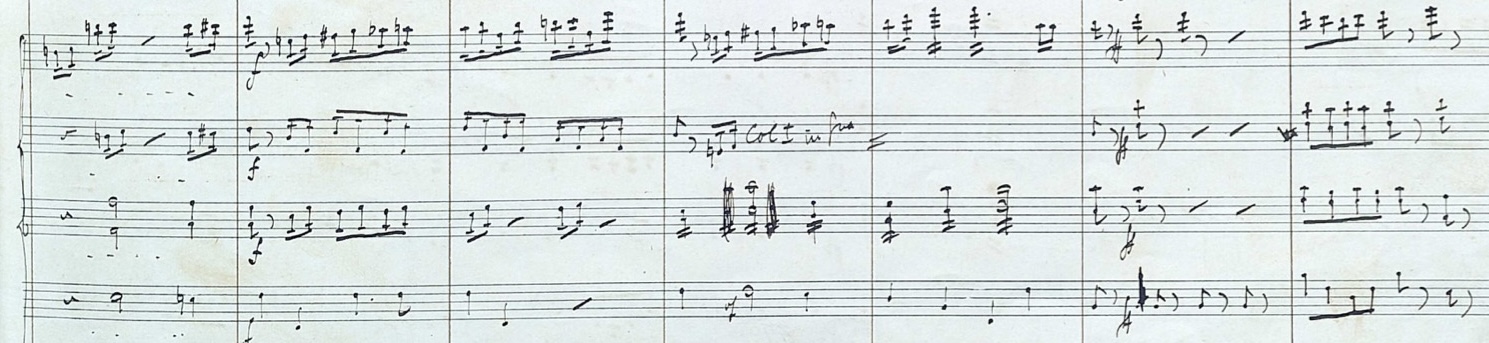

Yesterday, Sullivan noted in his diary “thinking about Overture”. I haven’t checked, but I don’t believe he had ever written those words previously! Today, he is “sketching Overture”, meaning he is plotting it out, choosing and editing the melodies from the show he plans to use, and putting it all together, in a light way, perhaps as a piano score (which doesn’t survive, if it ever existed).

Tomorrow, he begins “scoring Overture”. On 25 September he will lead the first band rehearsal for the new opera. “Very heavy work – could not get through it all.” I’m not surprised; Yeomen is the most complex and difficult to play of Gilbert & Sullivan’s comic operas, especially for the string players. Then he went back home to continue working on the overture. He finished it at 3:30 a.m. Frank Cellier called in on him at 3, somehow suspecting, I imagine, that Sullivan would still be at it. The next day he gives the score to his copyist George Baird, whose team will write out the orchestra parts.

For an overture, this is Sullivan devoting a considerable amount of thought, time, and effort. The results are astounding. This isn’t at all the usual overture—a medley of tunes from the show, stitched together with simple transitions. The Yeomen overture is a gem of (I’m going to say it) early 19th century music. It’s beautifully constructed in Sonata-Allegro form, which is the technical term for the structure of a first movement you’ll hear in most Symphonies by Mozart, or Beethoven, or Sullivan’s early influence, Mendelssohn. But Sullivan wasn’t writing a symphony here (many wish he had); the Overture runs at less than five minutes, about half of a typical Mendelssohn Allegro. Here the Allegro form is masterfully compressed. The Yeomen Overture can be enjoyed all on its own, even by people who are never going to listen to the full opera.

That’s enough dancing about architecture from me. If you haven’t heard it, go listen now and let me know your thoughts.

Here on 23 September, Sullivan dined at home, hosting his mistress Fanny Ronalds and her son, Reggie. Reginald Ronalds (1865-1924) is another fascinating character in Sullivan’s life.

In 1898, aged 33, he will leave his comfortable life in New York society to join the 1st United States Volunteer Cavalry, known as the Rough Riders. During the short-lived Spanish-American War, Lieutenant Colonel Theodore Roosevelt set out to form “a regiment of rough riders, western cowboys, and Indian fighters.” Reggie was none of those things, but he and a few chums from the exclusive Knickerbocker Club signed up anyway. He was with TR on San Juan Hill, in Cuba, without horses.

Hear Hear! One of Sullivan’s finest works. He was in fine form that year; the Macbeth overture is also a masterpiece of sonata form, and I’ve always thought the two overtures made an interesting pair of siblings.

Love the blog, please keep up the great work!

Thanks! My first comment that isn’t spam. Am I a real blogger now? 🙂

“This is a fact profoundly true!”