Before 1867, no one could have guessed that Arthur Sullivan would someday revolutionize musical theater in England—far from it. His background, his training, and his society connections all pointed to a different career.

Sullivan was born in South London in 1842, a time when serious classical music was dominated by European composers, conductors, and performers. Critics of the time frequently debated the “native talent question,” wondering whether British musicians would ever equal their European counterparts. During Sullivan’s childhood his father Thomas was the sergeant bandmaster at the Royal Military College at Sandhurst. Thomas obviously tutored the boy in music, as Sullivan later recounted that, before the age of 9 he learned to play “every wind instrument.”

In 1854 the 12-year-old Sullivan was accepted into the Chapel Royal, whose chorus master was impressed both with the lad’s musical training and fine singing voice. The Chapel Royal is an institution of composers and performers who serve the liturgical needs of the monarchy. In former times it was associated with the cream of English music–Bryd, Tallis, and Purcell–but by Sullivan’s day standards were not so high.

The chief duties of the boys was to sing at services in St. James Palace, but they also received musical instruction and tutoring in other subjects. It was during his time at the Chapel Royal that Sullivan started writing music. His first published song O Israel, a sacred song appeared in 1855.

The Chapel Royal also had a contingent of adult men singers including one “alto”—a high or counter-tenor voice—named John Foster. Remember this name; history has mostly forgotten him.

In 1856, at the age of 14, Sullivan was awarded the first Mendelssohn Scholarship to study at London’s Royal Academy of Music. He beat out 17-year-old Joseph Barnby for the prize; 22 years later Barnby and Sullivan would perform Sullivan’s Cox & Box together at a charity event in Switzerland.

Sullivan’s teachers at the Royal Academy included William Sterndale Bennett and John Goss, two of the most noted English composers of the day. John Foster directed the music at the Royal Academy banquets. Still singing with the boys at the Chapel Royal, Sullivan was designated “first boy” in the choir; Alfred Cellier, the future conductor of Gilbert & Sullivan operas, was second.

Two years later, Sullivan received his first notice in the English musical press. His Overture in D (now lost) was performed and mentioned in the journal The Musical World. After two years of study at the Royal Academy, the Mendelssohn Scholarship committee sent Sullivan to the Leipzig Conservatory for more advanced study, where he studied composition, counterpoint, conducting, piano and violin.

Sullivan was being groomed for greatness in the field of serious music.

Enter the Italian Terrorist

Just before Sullivan arrived in Leipzig, a strange incident occurred in France that had a profound effect on life in England for the next several years. On January 14th, 1858, an Italian named Felice Orsini attempted to assassinate the French Emperor Napoleon III by throwing a bomb under his carriage. The Emperor was unhurt, but rumors spread that the would-be assassin had planned the attempt and made his bombs in England. Anti-British fever swept the ranks of the French military, and several French officers petitioned Napoleon III to invade Britain.

An invasion seemed unlikely. France and Britain had close economic ties and had been allies against Russia during the recent Crimean War. On the other hand, the British public had not forgotten the invasion plans of Napoleon I, quashed in the naval battle of Trafalgar in 1805. The Crimean War and the 1857 rebellion in India had stretched the British military thin across the globe, leaving few regular army regiments left at home for defense.

Spurred by the press, in 1859 the British government sanctioned the formation of volunteer regiments. Six years later, this action would lead to Arthur Sullivan writing his first comic opera, Cox & Box, and ultimately to his collaborations with W.S. Gilbert, but the story takes several twists before we get there.

The Civilian Militias

In the beginning, little organization or guidance was offered to the volunteers. Local groups would form and perhaps find a regular military officer to command them; others elected their own regimental commanders. An example of the latter was the 38th Middlesex Rifle Volunteers, known as The Artists’ Rifles. This was the brainchild of one Edward Sterling, an art student and ward of Thomas Carlyle, the Scottish historian. In 1859 Sterling convened a meeting of some fellow students in the life class of Carey’s School of Art. One of these students was an amateur artist named Arthur Lewis. Remember this name.

In 1860 Sterling’s regiment was officially formed consisting of painters, sculptors, engravers, writers, musicians, architects and actors. Their badge, according to the regimental association, consisting of two heads: Mars-God of War, and Minerva – Goddess of Wisdom, was chosen to represent war and fine arts. The badge bore the motto Cum Marte Minerva which was also the title of the first Regimental March. A regimental rhyme records: Mars, he was the God of war, and didn’t stop at trifles. Minerva was a bloody whore, so hence The Artists’ Rifles.

Early members of the regiment included artists Val Prinsep, Frederick Leighton, William Morris, Holman Hunt, Dante Rossetti and John Everett Millais—the last three the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood of artists–and the poet Swinburne, all of whom would later be lampooned in Gilbert & Sullivan’s Patience. Another regiment, one of the Somerset House Companies included Gilbert himself, who eventually reached the rank of Captain.

Despite their good intentions, the volunteer regiments were treated with a great deal of scorn by the regular army which considered them next to useless. They were frequently the butt of jokes in literary magazines (see the drawing from Punch). The feared French invasion never materialized, and after a while the scare died out. Many of the men, however, made life-long friendships during the days of the volunteer movement.

This was especially true of Arthur Lewis. Born in 1824, Lewis was co-owner of the successful silk merchants Lewis & Allenby (later mentioned in Princess Ida). Through his study of art and his participation in the Artists Regiment, by the early 1860’s Lewis enjoyed the friendship of many eminent and rising men of the arts. Sometime around early 1860, Lewis began to invite his friends to his London apartment in Jermyn Street to smoke, drink, and sing songs. This fostered the formation of an amateur men’s choir, The Jermyn Band, led by Mr. John Foster, now a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal (remember him?).

Boy Wonder

At the same time, young Sullivan studied for three years at the Leipzig Conservatory, and for his graduation concert in 1861, he composed and conducted a suite of incidental music to Shakespeare’s The Tempest. Two musical papers in Leipzig were impressed. A year later, Sullivan’s Tempest was performed in London at one of the famous Crystal Palace concerts. Suddenly, Sullivan was a sensation. “He, and those who first discerned the germs of talent in him, may well be proud” wrote The Times. The weekly Athenaeum beamed “it may mark an epoch in English music, or we shall be greatly disappointed.” Strong praise for a young man who had not yet reached his twenty-first birthday.

Sullivan built on his new celebrity, composing several more serious works in the following years. In 1863 he contributed three pieces to the wedding of Edward, Prince of Wales—a singular honor for a young composer. Also that year he wrote his first opera, The Sapphire Necklace—this was never produced but its overture was performed and well received—and wrote his first and only symphony, now known as the Irish Symphony. The oratorio Kenilworth followed in 1864, conducted by Michael Costa, England’s foremost conductor. Sullivan seemed destined to prove that musical genius could indeed come from Albion’s shores.

Also in 1864, Sullivan got his first position as a conductor, of the newly-formed Civil Service Musical Society. This was an amateur group formed officially by Sir W.H. Stephenson, the head of Britain’s tax service, but was more likely the brainchild of Sullivan’s college friend, the composer Frederic Clay. Sullivan was appointed the society’s first orchestral conductor, John Foster (remember him?) its choral conductor.

The Moray Minstrels

In 1863, Arthur Lewis, that great connector of artists in all fields, founded The Arts Club in London, with a membership of 250 including many members of the Artists Regiment and several artists and writers of the satiric weekly Punch. By this time Lewis had moved from Jermyn Street into Moray Lodge, a large house on Campden Hill in Kensington, which was then a pleasantly rural part of London.

The Jermyn Band continued to thrive; the group was 21-man strong and was still led by John Foster, who would continue to conduct the group for another 40 years. Sullivan would later write that the men “were all picked voices and they really sang to perfection.” After Lewis’s move to Moray Lodge, the group was rechristened The Moray Minstrels.

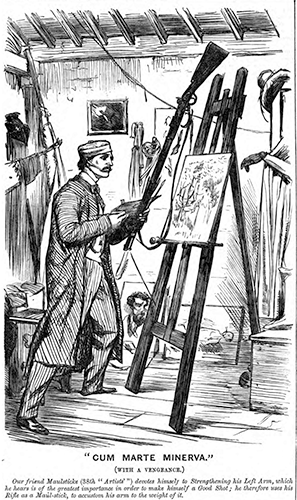

The Minstrels sang not only for their own enjoyment, they also performed publicly, often at charity benefit events. Music critics of the time praised the group’s professional level of performance. By 1865, Lewis was hosting the Minstrels in concert at Moray Lodge four times per year, on the last Saturday of the month from January through April. These were large events, with 150 or more gentlemen attending. Attendance was by invitation, and the artist Frederick Walker designed and printed tickets. The invitation for 1865 includes caricatures of several habitués of these events, including the 23-year-old Sullivan.

Moray Minstrel evenings began with a concert of chorales and chamber music. This was followed by a buffet dinner which featured oysters. Smoking was also a distinguishing feature of the event, making the evenings inappropriate for ladies. In 1867, Arthur Lewis married the actress Kate Terry—their grandson was the actor Sir John Gielgud—and thereafter the concerts evolved into more genteel garden parties, with ladies invited.

After supper, the guests were invited to tell stories or perform skits and music. At the Moray Minstrel evening on March 25, 1865, two Punch contributors, Harold Power and George du Maurier (the grandfather of novelist Daphne) performed Jacques Offenbach’s one-act operetta, Les Deux Aveugles (The Two Blind Men). By all accounts they were hilarious.

Sullivan was there that night, as was Francis Burnand, another Punch author. Legend has it that, either at this evening or another in 1866, someone suggested to Sullivan that he write something new for Power & du Maurier to perform.

Enter Box & Cox

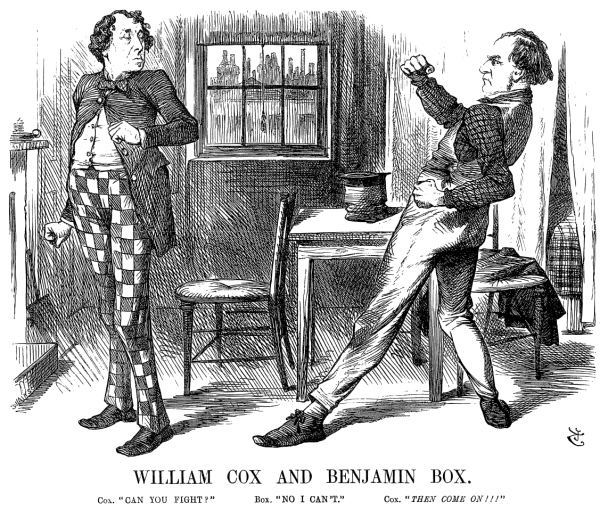

Burnand later wrote that it was his idea, and that he also suggested the play to set, John Maddison Morton’s farce Box & Cox. History is vague on who truly suggested what to whom, but the Morton play was tailor-made for a Moray Minstrels adaptation. It was short, only one act; it could be staged with household furniture; and it contained only three characters, two men, one woman. It was also the most popular farce, perhaps the most popular English theater piece, of the 19th century.

The plot involves an unscrupulous landlady who has rented a room to two young men, one who works all day and the other all night. Neither realizes they are in fact sharing the room. When one gets a rare day off from work, the two finally meet and hilarity ensues.

By 1865, Box & Cox had been playing in various productions for nearly 20 years. It would continue to play into the early 20th century.

Box & Cox becomes Cox & Box

Sometime in 1866 Sullivan & Burnand started work on Cox & Box (Burnand inverted the title of Morton’s work), but it wasn’t performed at a Moray Minstrel evening until April 27, 1867. Sullivan played the piano while Power and du Maurier performed the roles of Cox and Box, and Minstrels leader John Foster (remember him?) portrayed the third character, Bouncer the landlord. Due to the all-male party, Burnand transformed Morton’s landlady into “Sergeant Bouncer, Late of the Dampshire Yeomanry, with military reminiscences.”

The fact that Bouncer was a former military volunteer would have tickled the Moray Minstrels audience, many of whom were veterans of The Artists’ Regiment. After being laughed at in 1860 for being incompetent would-be soldiers, now they could laugh at themselves and remember their own military “glories.” Indeed Cox & Box’s first song is Bouncer’s Rataplan, in which he recounts how he bravely mounted a horse in her Majesty’s force / As one of the yeomen who’d meet with the foemen/For then an invasion threatened the nation! In dialog Bouncer refers to Cox variously as Mister, Captain, Colonel, and Brigadier Cox, echoing a time when no one was sure who was in charge of what.

Not long before the Moray Minstrel evening of April 1867, a Punch artist, Charles Bennett, passed away at the age of 38, leaving eight children and a pregnant wife. The Minstrels, Sullivan and the Punch men decided to produce a charity performance for the benefit of Bennett’s family. That show took place on May 11, 1867 at London’s Adelphi Theatre and included performances by the Moray Minstrels, conducted by John Foster; plays performed by the Punch men, augmented by the acting sisters Ellen, Kate, and Florence Terry; Power and du Maurier’s performance of Les Deux Aveugles (in French); and the public premier of Sullivan & Burnand’s Cox & Box, performed for the first time with orchestral accompaniment.

Of Cox & Box the Musical Times wrote:

[…] we feel compelled to say that Mr. Burnand has executed his task so well, and that Mr. Arthur S. Sullivan, our most rising composer, has written music so full of sparkling tune and real comic humour that we cannot but believe that this version of a widely popular farce would have a new genuine success if produced on the recognized stage by recognized professional players. It is quite as stirring and lively as anything by M. Offenbach, with the extra advantage of being the work of a cultivated musician […]

(emphasis mine)

A second performance, on May 18, 1867 was attended by W.S. Gilbert, who wrote in Fun magazine:

Mr. Burnand’s version of Box and Cox—which he calls Cox and Box—is capitally written, and Mr. Sullivan’s music is charming throughout. The faults of the piece, as it stands, are twain. Firstly: Mr. Burnand should have operatized the whole farce, condensing it, at the same time, into the smallest compass, consistent with an intelligible reading of the plot…. Secondly, Mr. Sullivan’s music is, in many places, of too high a class for the grotesquely absurd plot to which it is wedded. It is very funny, here and there, and grand or graceful where it is not funny; but the grand and the graceful have, we think, too large a share of the honours to themselves.

Thus was born a lifetime of rivalry between Gilbert and Burnand, which Gilbert obviously got the better of.

On March 29, 1869, Cox & Box received its first profession production, at the Royal Gallery of Illustration. It shared the bill that night with the one-act operetta No Cards, penned by Gilbert with music by old Sullivan chum Frederic Clay—the first time the names Gilbert & Sullivan appeared on a program together, albeit not yet as collaborators. Gilbert later wrote that he first met Sullivan during a rehearsal of his next operetta, Ages Ago, also with music by Clay.

Though the partnership we now know as Gilbert & Sullivan was not launched until two years later, with Thespis at the Gaiety Theatre, something had happened to Sullivan. The young, rising, cultured musician who had been trained to become Britain’s best hope for native musical greatness was exposed to the glitzy and profitable, though decidedly less-respectable world of musical theater.

It may be argued that his interest in theater music was evidenced earlier with his setting of The Tempest, but until that fateful performance of Les Deux Aveugles at the Moray Minstrels evening in 1865, Sullivan had shown no indication that he would become Britain’s most successful composer of comic opera.

For the rest of his life Sullivan would wrestle with the question of how best to direct his talents, into serious work or popular opera, with critics frequently upbraiding him when he chose the latter. Even his obituaries complained that England’s golden boy had sold his soul. Writing anonymously in 1890, George Bernard Shaw mocked those critical voices.

Everybody knows Pinafore and The Gondoliers and all that between them is; so that now the first of the Mendelssohn Scholars stands convicted of ten mockeries of everything sacred to Goss and [Sterndale] Bennett. They trained him to make Europe yawn; and he took advantage of their teaching to make London and New York laugh and whistle.