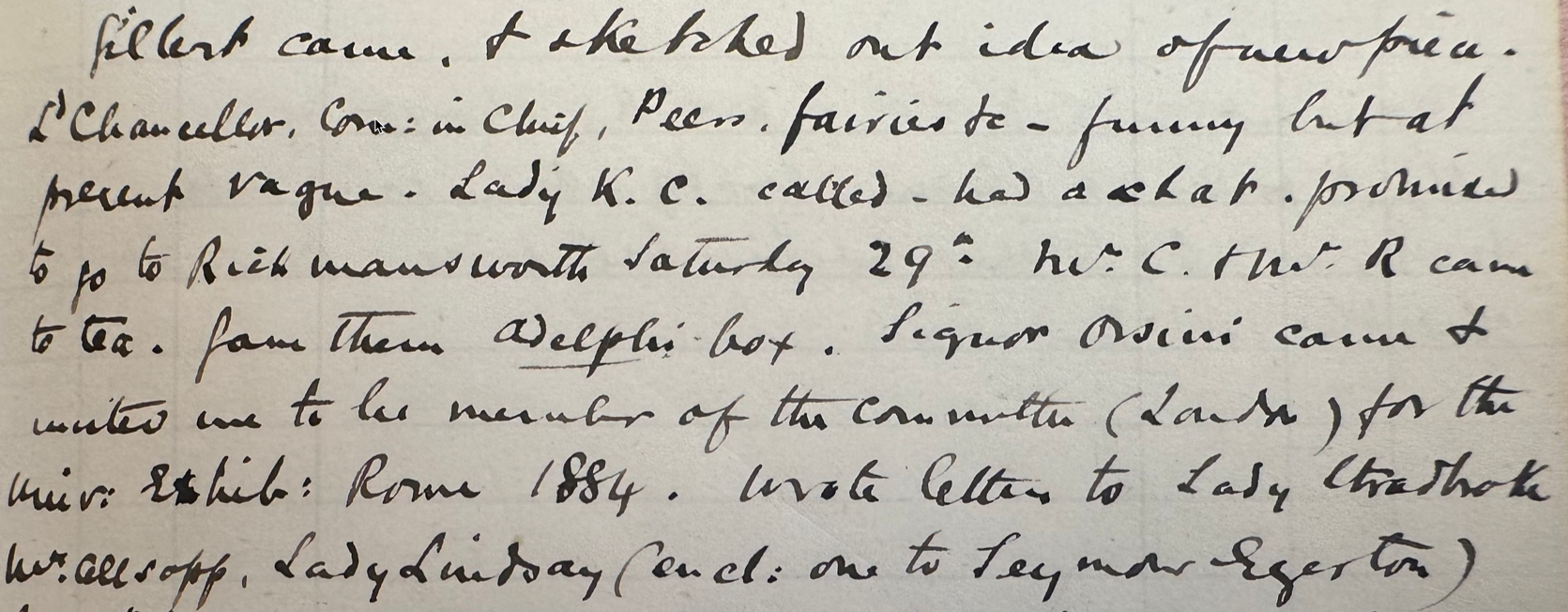

In my last post on Sullivan’s diaries, I claimed that the only way to positively know when a keyword has made its final appearance in Sullivan’s diaries is to read every subsequent word of every subsequent day of every subsequent year. In a world of Ferraris and easy text searching, this sounds like buggy whip talk. But you’ll know it’s true when I explain that Sullivan’s writing is very … what’s the word? … hmmm … let’s go with idiomatic. Because sloppy sounds so judgmental.

However we describe it, to date no one has built a machine learning recognizer capable of transcribing the diaries. I believe that could be done, if not today then very soon. But so far, we don’t have any software which will convert Sullivan’s diaries into human-readable, searchable text. Hence every time you read a reference to any entry from a Sullivan diary, that reference has come either from the brain of a human who read it and transcribed it, or from someone who trusted a previous human’s transcription enough to quote her. Most of those humans were historians and writers, interested in learning about the life of Sullivan, and each reader had their own interests and reasons for reading the diaries.

But there was one human with a grander plan. His name was Geoffrey Dixon. And I’m going to liberally quote from his obituary, written in 2009 by Maureen Elizabeth MacGlashan, CMG.

Imagine, it’s the 1960s, and you are the chief cataloguer at Ipswich Public Libraries, enjoying the challenge and satisfaction of “bringing some sort of order to chaos”. Time passes, and as your career flourishes, you move to Manchester, then to Ayr in Scotland, where you win the post of principal librarian at the Craigie College of Education (now part of the University of the West of Scotland). Being very interested and experienced in indexing, you join the Society of Indexers. You become one of that society’s first Registered Indexers. You make frequent contributions to their journal, The Indexer. You become literally the indexer of The Indexer. You edit a Rapid Results College correspondence course, in indexing. And, you happen to love the works of Gilbert and Sullivan.

What might you do?

If you are Geoffrey Dixon, you set out to bring some order to the chaos of studying Gilbert and Sullivan. As a member of both the Sir Arthur Sullivan Society and the Gilbert & Sullivan Society, Dixon could see that much important research was being published in society magazines which was difficult to find and cite due to a lack of indexing. What to do?

From the magazine of the Sir Arthur Sullivan Society, No. 37, Spring 1993:

GILBERT AND SULLIVAN CONCORDANCE

Contrary to the Editor’ s misinformed statement (Mag 36 p.15) Isaac Asimov’s Annotated Gilbert & Sullivan is not the largest G&S book ever published. Mr Geoffrey Dixon writes that his own Gilbert And Sullivan Concordance is both longer and heavier. […]

“A quoted context is given for each occurrence of every word, together with an indication of where it can be found in the full text.”

From the magazine of the Sir Arthur Sullivan Society, No. 41, Autumn 1995:

INDEX TO THE SULLIVAN SOCIETY MAGAZINE Nos 1-40

By Geoffrey DixonGeoffrey Dixon is a Life Member of the Sullivan Society and a retired Member of the Society of Indexers. He therefore brings professional expertise and long experience to this magnificent Index to the first 40 issues of the Sullivan Society Magazine (1977-1995).

Also, from that same edition:

THE GILBERT AND SULLIVAN PHOTOFINDER

An Index To Published Illustrations Of Savoy Opera

By Geoffrey DixonAt 234 pages the Gilbert and Sullivan Photofinder is a comprehensive work which covers not only the familiar Savoy operas but also operas written separately by Gilbert and Sullivan, together with Gilbert’s plays, and places and persons connected the two men.

Then, from the magazine of the Sir Arthur Sullivan Society, No. 42, Spring 1996:

THE GILBERT & SULLIVAN JOURNAL 56-YEAR INDEX

By Geoffrey DixonFollowing on his admirable Index to the Sullivan Society Magazine and The Gilbert & Sullivan Photofinder, Geoffrey Dixon has undertaken the mountainous task of indexing the Gilbert and Sullivan Journal from 1925-1981.

Then, from the magazine of the Sir Arthur Sullivan Society, No. 53, Autumn 2001:

The Gilbert and Sullivan Sorting System – a classification scheme for use with the materials of G&S Studies.

By Geoffrey Dixon.This enormously competent and comprehensive work may be described as a search engine for G&S studies. The author proposes a classification scheme, like the Dewey system, for all aspects of the subject, together with examples of how to use it.

The Man is an Indexing Machine

These are truly impressive works of indexing. It’s just too bad that today, they are largely useless, since we can all now scan, OCR, search, and index typewritten documents to our hearts’ content. But then, in the magazine of the Sir Arthur Sullivan Society, No. 61, Winter 2005:

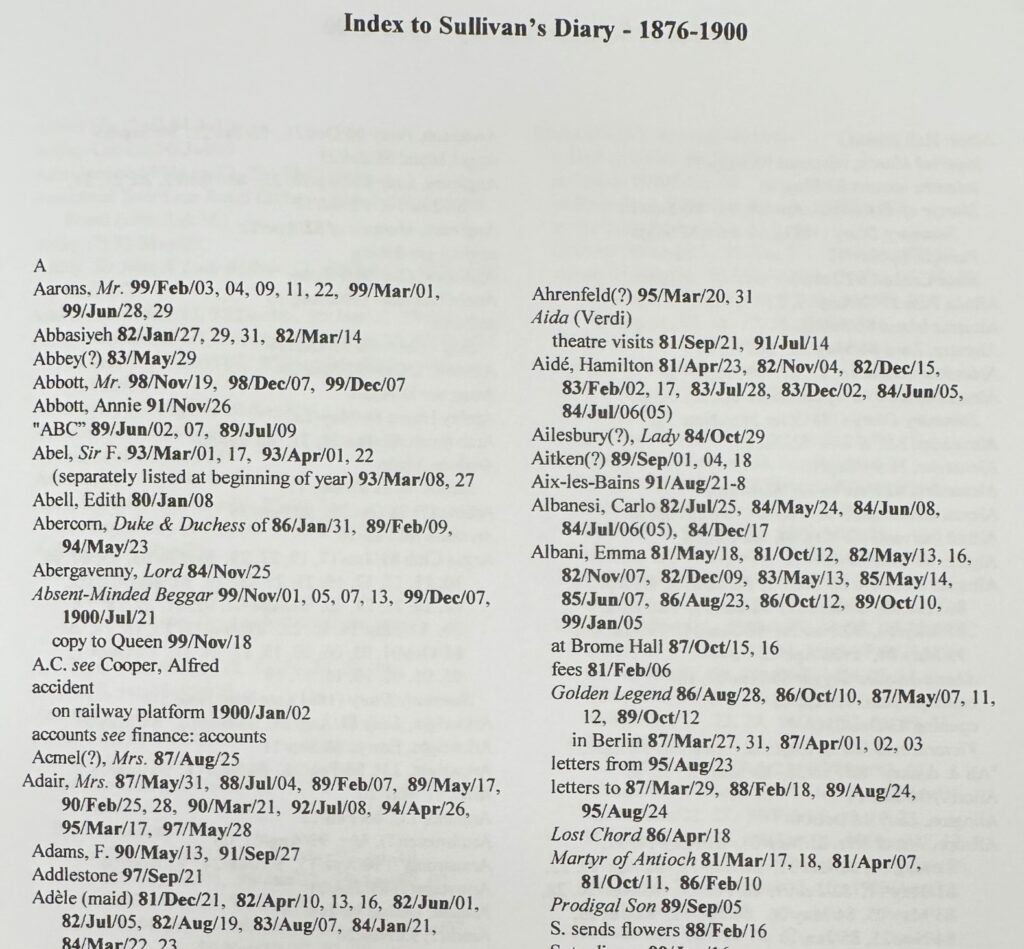

INDEX TO SULLIVAN’S DIARIES

Geoffrey Dixon (author of The G. & S. Concordance, The G. & S. Sorting System, The G. & S. Photofinder, etc.) has been engaged for some time in compiling an index to Sir Arthur Sullivan’s diaries and is now about three-quarters of the way through. He hopes eventually to publish the completed index but in the meantime wishes to invite anyone who would like to consult such an index to get in touch with him if they think he could be of help. He points out in passing that, as well as the torrent of personal names in which the diary abounds (Sullivan seemed intent on recording everybody he met – especially the aristocrats!), there are plenty of interesting avenues of enquiry – such as 1) the number of times he went to the theatre as a member of the audience and the sort of productions he saw, or 2) the number of visits he made to his favourite clubs, or 3) his health problems. The completed index will cover all 20 volumes of the diary (1881-1900) held in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library of Yale University. It is hoped that the other two volumes (1879 and 1880, held by the Pierpont Morgan Library, New York) will be added at a later date.

In 2007, Dixon releases his masterpiece.

Dixon has attempted to decipher and index every person, place, thing, and concept from all of Sullivan’s diaries and place them into a coherent index, usable as a book. Today, his index is frequently cited in Sullivan research. Because, as I said, even today, the only way to locate keywords in Sullivan’s diaries is to either scan every entry of each and every of 20 years … or … thanks to Dixon, look up that keyword in his index.

Is it useful?

You bet it is! But there are limitations. This is a monumental work of scholarship. I never had the pleasure of meeting Mr. Dixon, so I can’t tell you how he managed it. I can say that he clearly had an extensive knowledge of Sullivan’s life and times. But he worked alone, and he didn’t have the Internet we have today. Sullivan’s handwriting is challenging to interpret, and having a team of readers might have helped him decipher more words. Words that occur only once or twice in the diaries can be unintelligible. The modern Internet helps us to better understand obscure words because so much new historical content becomes available every year. This is especially true when trying to connect Sullivan to the names of other people.

The result is that the index is neither complete nor fully accurate. In a recent post, I wrote about Herbert Sullivan’s time working for the Brush Electrical Engineering Company, in Loughborough. I took all of my data from Sullivan’s diaries. Dixon’s index contains neither the words Brush nor Loughborough. This happens not infrequently.

Then there’s the problem of presenting this data in book form. Mr. Dixon worked in a time when indices were printed. In 2007, it would have been more useful to have published this data in some digital form. A searchable database would have been ideal, but even an OCR’ed PDF would be handy. Instead, there is no digital form of the index available, and hence no way to search the index itself.

Even worse for us today, Dixon’s books were self-published, and they had a very small market of readers. It’s nearly impossible to obtain a copy of Dixon’s book today (believe me, I’ve tried). Fortunately several large libraries hold copies, including Yale’s Beinecke Library, and the Library of Congress. I know I’m not the only one to have photographed the index for personal research, but sharing those photos online would be a violation of Dixon’s copyrights, which I presume are held by his heirs.

But don’t get me wrong, Dixon’s index is a treasure. If he were here today, I’d be honored to buy him several pints and pick his brain.

[…] Nothing. I am not aware of a single mention of Cunningham or Christopher Bridgman or Bridgeman in the diaries. He isn’t listed in Geoffrey Dixon’s index. […]