Fans of Gilbert & Sullivan shows often enjoy debating the merits of one opera versus another.

Too often in those discussions, I hear the opinion expressed that most, perhaps all of the fourteen Gilbert & Sullivan collaborations were both superior to and more successful than the SWOGs and the GWOSs.

What is a SWOG? That’s Sullivan without Gilbert. A GWOS? Yup, you get the idea. During their careers, both Sullivan and Gilbert produced operas with other lyricists and composers. Few of those works are regularly performed today, but that fact does not mean they weren’t successful in their day, or that they are artistically inferior.

The story of Gilbert & Sullivan, in a nutshell

The collaboration known as Gilbert & Sullivan began in 1871 with the show Thespis. Their shows were hugely successful from 1878 to 1890, and they disbanded in 1896. From 1871 to 1890, Sullivan wrote comic operas only with Gilbert. Likewise, from 1877 to 1890, Gilbert wrote opera libretti only for Sullivan. Then in 1890, the pair had a rather nasty falling out (see The Carpet Quarrel).

Hence the SWOGs and GWOSs date from two timeframes: the period before Gilbert & Sullivan found great success as a team, and the period following their last great collaborative success, The Gondoliers, in December, 1889.

The Early SWOGs

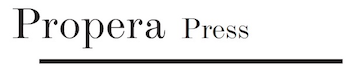

The early period SWOGs include Sullivan’s first three comic operas, Cox and Box (1866), The Contrabandista (1867), and The Zoo (1875). Of those three, only Cox & Box achieved lasting success, and it is the most revived today, mostly by amateur groups in the US and UK. As a one-act opera, it is sometimes paired with The Zoo to create a two-act performance. The Zoo lapsed into obscurity, and for many decades its music was lost. As for The Contrabandista, it was forgotten as well, until 1894, when Sullivan unsuccessfully tried to revive it, in a new version entitled The Chieftain. Modern performances of The Contrabandista, or The Chieftain, are very rare.

The Early GWOSs

During Gilbert’s early period he collaborated with several composers and achieved some success with the composer Frederic Clay, a close friend of Sullivan. Gilbert & Clay’s biggest hit was the comic opera Ages Ago (1869). It was one of six comedies Gilbert produced for the small Royal Gallery of Illustration theater; musically, its singers were accompanied only by piano, harmonium and harp. None of the six Royal Gallery shows are regularly performed today.

The Post Break-up

The period after Gilbert & Sullivan’s huge successes, and their break-up—the years 1890 to 1900—is more interesting. By 1890 both men were famous and wealthy. Both had many offers and opportunities to work with other collaborators. But their differing dispositions set the two gentlemen in different directions.

Gilbert, Post Break-up

Gilbert, the older of the two, was also the most prolific, producing dozens of operas, plays, poems, and magazine pieces. By 1890 he was ready to plan for retirement. He bought Grim’s Dyke, a country estate northwest of London which would be his home until his death in 1911. Today, it’s a hotel. He made large investments, including the building of the new Garrick Theatre in London, a successful venue which is still hosting plays today.

Gilbert no longer needed to work. But after his split with Sullivan, he nonetheless dove immediately into a new project, partnering with the composer Alfred Cellier (another long-time Sullivan friend) to produce The Mountebanks in 1892. The lengthy gestation of this opera was due to the illness and untimely death of Cellier.

But The Mountebanks found success on the stage and is today the best known of the GWOSs. There is a modern recording of the music, and it occasionally sees an amateur production. Gilbert’s later operas without Sullivan include Haste to the Wedding (1892), His Excellency (1894), and Fallen Fairies; or, The Wicked World (1909). Of those, only His Excellency found any popularity. Gilbert had offered its libretto to Sullivan—one of the great “what ifs” of G&S lore—but Sullivan refused to set it after Gilbert insisted that his protégé Nancy Mackintosh be cast as lead soprano.

In sum, Gilbert’s post-Sullivan operas did not achieve the popularity of those of Gilbert & Sullivan, but financially, and in artistic reputation, Gilbert was already set for life.

Sullivan, Post Break-up

Unlike Gilbert, whose life’s work was always in the domain of popular culture, Sullivan aspired also to the reputation of a composer of serious works. His training and early works had been dedicated to serious music. (To see how he became entangled in musical theater, see A Tale of Cox & Box — Or How an Italian terrorist gave rise to Gilbert and Sullivan.) During the peak G&S years, he was still known as a conductor of prestigious music festivals, and an occasional composer of choral works (The Martyr of Antioch in 1880, and more famously, The Golden Legend in 1886). But by 1890 it had been 20 years since his last major, non-choral orchestral works.

For many years he longed to create Grand Opera, produced with proper professional opera singers and a large orchestra, setting to music a libretto which would allow him free rein as a modern composer of serious music. He got that opportunity in 1890, after his friend and business partner Richard D’Oyly Carte undertook to build a new theater for grand opera in London. Carte was the producer and investor behind the G&S phenomenon, as well as the developer of the Savoy Theatre and Hotel. Producing Gilbert & Sullivan, and creating luxury hotels and restaurants had made him very wealthy.

The success of the new opera house was anything but assured; London already had three venues for grand opera (the Royal Opera House, Her Majesty’s Theatre and the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane) and none of them were particularly over-used. For the inauguration of the Royal English Opera House, Sullivan created the grandest of the SWOGs: the opera Ivanhoe, based on the novel by Sir Walter Scott. Meanwhile, Carte tried to persuade other English composers to create new works for the Royal English Opera.

Ultimately, neither Ivanhoe nor Carte’s dream of a new palace for English grand opera long survived. The business closed a year later, and Carte sold the building, ending the experiment.

Sullivan expressed fatigue with the comic, topsy-turvy world of Gilbert, and sought out new stories to set to music, with more human drama. But after one attempt—1892’s Haddon Hall—Sullivan instead spent the next four years trying to recapture financial success via renewed partnerships with Gilbert and Francis Burnand, his collaborator on Cox & Box so many years ago. Sullivan’s final two works with Gilbert, Utopia, Limited (1893), and The Grand Duke (1896), kept him afloat but failed to renew the remarkable incomes of their previous shows.

In 1898, Sullivan faced a financial crisis. Contemporary letters and his diary entries suggest he became delinquent in loan repayments to Lloyds Bank, and may have been threatened with bankruptcy proceedings. At the same time, he was working on another SWOG, The Beauty Stone, which he almost certainly knew would not pull him out of financial danger. The show was the worst failure of Sullivan’s career; soon after its premiere, he left Britain for Austria to improve his health, and to begin the search for another collaborator. Sullivan was now dedicated solely to making money.

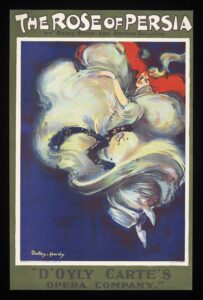

His search eventually led Sullivan to Basil Hood, a retired army captain who had spent the 1890s writing an impressive string of successful musical comedies. Hood proposed an idea for a show based on the character of Abú al-Hasan—“The Sleeper”—from the One Thousand and One Nights folktales, and the two began work. The result was the comedy The Rose of Persia (1899), the one clear winner among the SWOGs.

The Times of London wrote:

It is a long time since a success like that of The Rose of Persia has befallen the management of this theatre; and in fact it may be said that since the days of The Mikado it is not easy to point to a first night that has pleased everybody, including those whom it is best worth while to please, whether from the artistic or the financial point of view. An extremely well-contrived libretto, in which various motives from the “Arabian Nights” are combined with excellent effect by Captain Basil Hood, has been set by Sir Arthur Sullivan with all the spontaneity and refinement of his earlier years, and the result is an entertainment that yields to none of its predecessors in charm or brightness.

Rose ran in London from November 29, 1899, through June 28, 1900. It toured throughout the UK and Ireland for over a year, until at least August 3, 1901. It was licensed for productions in America and in Australia, making it the first Sullivan opera to be produced outside of the UK since the short, disastrous run of Utopia, Limited in New York. The Berlin Central Theatre even licensed Rose for a production.

In Australia, producer J.C. Williamson had passed on both Utopia, Limited and The Grand Duke, but made a lavish spectacle out of Rose, even adding a “Persian Grand Ballet,” danced by 24 ballerinas, with music by conductor Leon Caron. Rose enjoyed short but profitable runs in Sydney and Melbourne. Its reception in America was less enthusiastic, but Rose played in New York, Baltimore, and Washington DC. Several American critics placed the blame for its limited success not on the show but upon its performers.

The Rose of Persia reestablished Sullivan’s reputation as Britain’s preeminent composer of comic opera. And it started to refill his bank account.