Part 4 of 3.

It’s entirely possible that you, Dear Reader, have now heard more than enough about young Herbert Sullivan’s failure to launch a career. (That story begins here.) This post is inspired by my accidental discovery of new information for that story—I do owe Bertie a partial apology—and a realization that most people have never seen a Sullivan diary and have no idea why they can often be so difficult to study.

In Part 3 of this series, I recount how, after several false starts, in 1892 Herbert appears to have landed a position with the Brush Electrical Engineering Company, in Loughborough. I say appears because I admit that conclusion is based on circumstantial evidence. Bertie had previously worked for engine and electrical companies, and for a time he was spending his working days in Loughborough. Then, around November 1892, references to Loughborough in Sullivan’s diaries appear to end.

Again I’ve just written appear. Why can’t I be more definitive?

Our sources for the Life of Sullivan

Sullivan wrote very little about himself for public consumption. He wrote no long memoir. The closest to that sort of thing is the book Sir Arthur Sullivan: Life story, letters, and reminiscences, by Arthur Lawrence, published just a few months before Sullivan’s death. For that book Sullivan gave Lawrence access to many personal letters (especially from his Mum) and several hours of interviews. In return, Lawrence gave Sullivan a level of review that today feels like editorial control. The result is mostly hagiography, although it does give us some glimpses into how Sullivan remembered his life, and how he wanted to be remembered. I do not believe he let Lawrence read his diaries.

After Sullivan’s death, some colleagues and family members published biographies. But only one of them had possession of Sullivan’s surviving papers, letters, and diaries: Herbert. I say surviving because Arthur Sullivan had a habit of destroying most of the correspondence he received, as well as virtually all of his unpublished music and preliminary sketches. The most staggering loss in this area is his correspondence with his mistress Fanny Ronalds. For at least the last 20 years of Sullivan’s life, he spent some time with Fanny on many (perhaps most) of the days they were in the same place, and when they were not together they exchanged letters and telegrams—sometimes more than once each day. Both of them paid such scrupulous attention to their reputations that today only a single example of those letters survives. And it’s a tourism report from Sullivan.

Hence for would-be Sullivan biographers in the early twentieth century, the sources for a Life of Sullivan consisted of personal anecdotes, some surviving letters written by Sullivan to others, and press articles. All except for Herbert—he had Sullivan’s diaries. In 1927 Herbert partnered with the publisher and author Sir Walter Newman Flower to produce the book Sir Arthur Sullivan, his Life, Letters & Diaries. This was the first Sullivan biography to use the diaries as the spine of a life narrative. Sullivan and Flower included many excerpts from the diaries, revealing them to the public for the first time. Subsequent biographers liberally cited Herbert’s book, and for many years no one else had access to the diaries themselves.

Herbert died in 1928 and all of Arthur Sullivan’s papers went to Bertie’s widow, Elena. She remarried soon after, becoming Mrs Elena M. Bashford. She lived until 1957. In the late 1960s her heirs sold Sullivan’s surviving manuscripts and papers, including the diaries, to libraries and private collectors. The diaries for 1881-1901, plus an account book from 1879, ended up at Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library. (The 1901 diary was written by Herbert.) The Morgan Library in New York contains three slimmer volumes, dating from 1858, 1867, and 1875-1880.

These library acquisitions finally made it possible for scholars to read Sullivan’s diaries. But possible doesn’t mean easy. Even today there are several hurdles to studying them.

How to read a Sullivan diary

To start with, there are no publicly available images of the pages of Sullivan’s diary. The Beinecke Library made microfiche copies many years ago, and I believe there are a few copies of those floating around. But if you want to read the original books, or their microfiche, you need to visit the library. The diaries are not in circulation, of course, nor even on shelves. They must be reserved by a researcher and read in the library’s reading room. The library is quite beautiful and comfortable, and the staff there are professional and very nice folks.

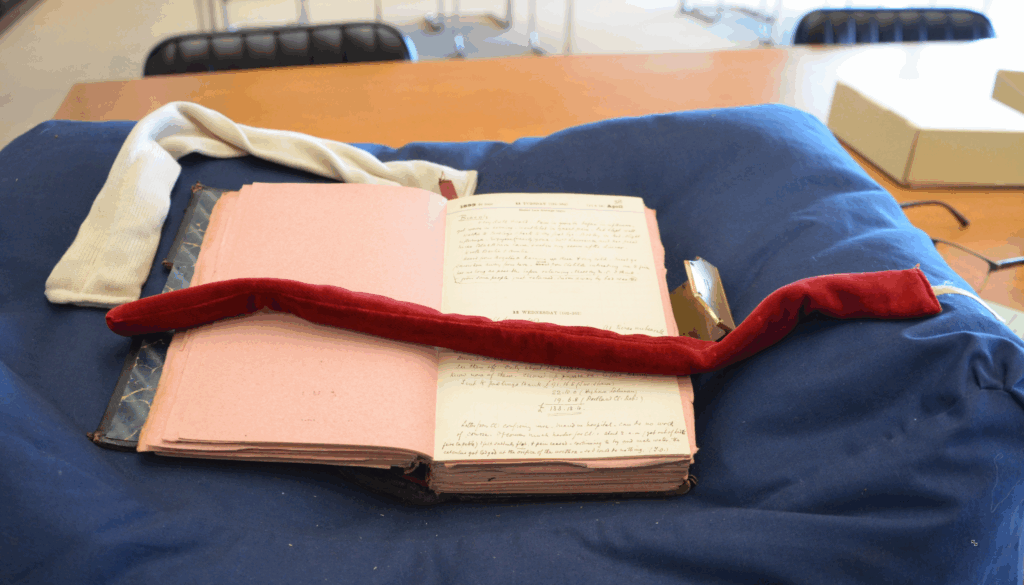

After getting permission to peruse the diary, and traveling to New Haven, Connecticut, we check into the library through security (after having locked everything we brought into a locker and having placed our laptops in a plastic, see-through bag). We are given the book we requested, with a little pillow to protect it and some “snakes” to hold it open. We settle into a desk.

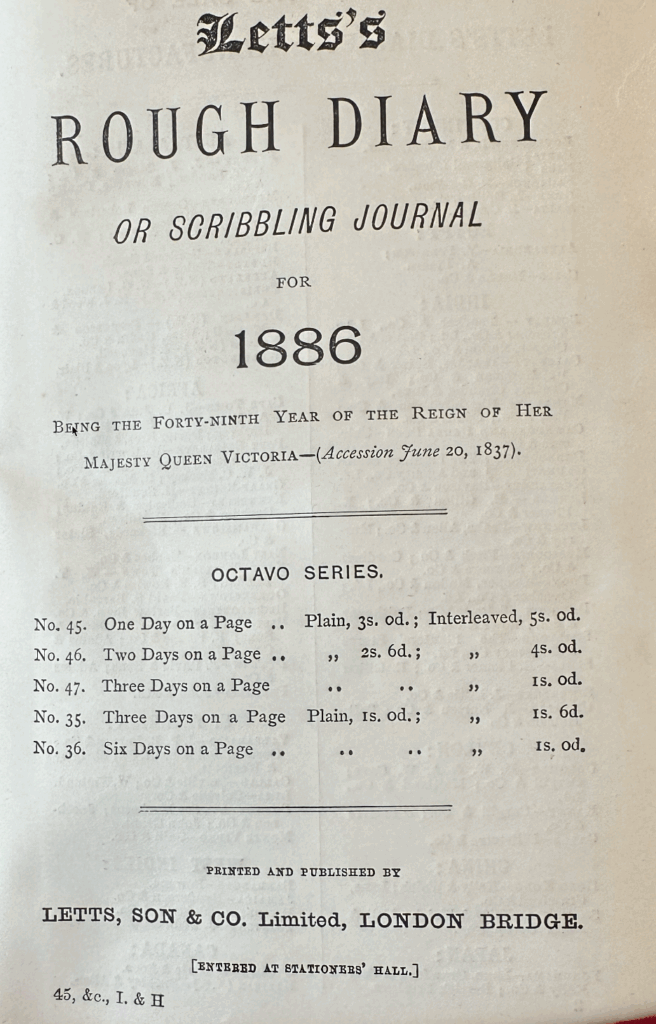

Sullivan had a preferred brand of book he used. They were substantial, heavy, well bound with an embossed gold title on the spine, and a lockable leather strap. It is apparent that Sullivan left them locked because today the straps are broken. Opening the diary, we see that it included preliminary pages for notes and correspondence, and end pages for accounts. The main pages present days of the year with helpful data such as holidays, liturgical dates, hunting and court schedules, even phases of the moon. Each writing page is separated from the next one with a sheet of blotting paper. Sometimes you find little nuggets on those blotting sheets. On 25 August, 1884, Sullivan used his diary to blot a short note he sent to … someone:

Then we reach the next hurdle: actually reading what Sullivan wrote.

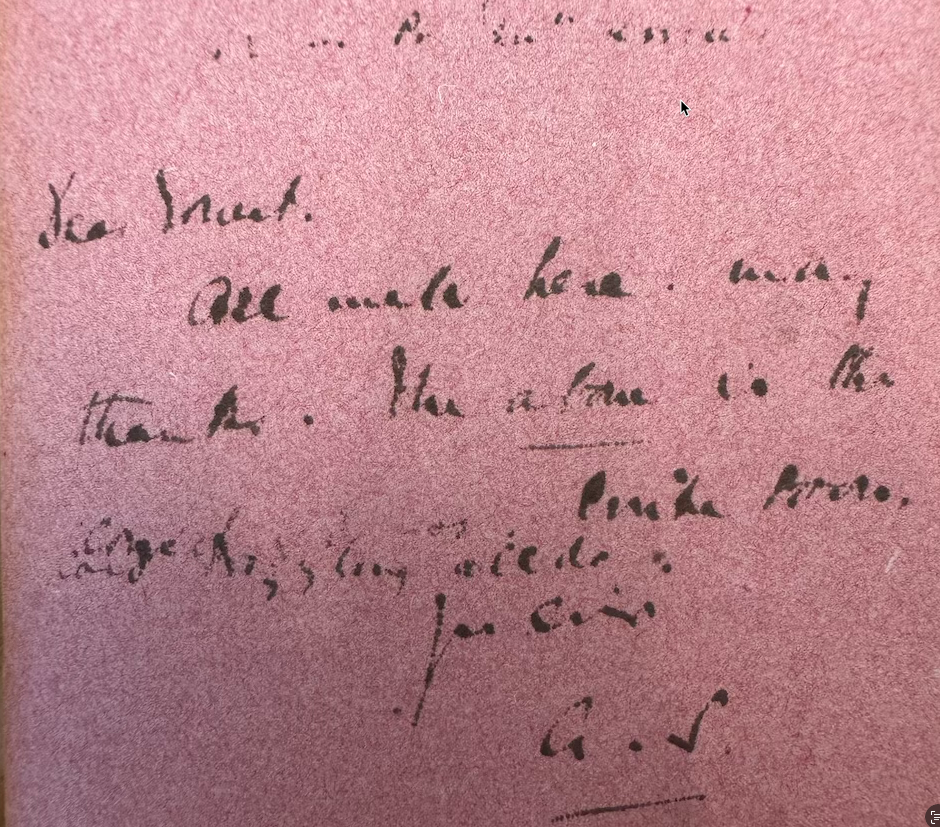

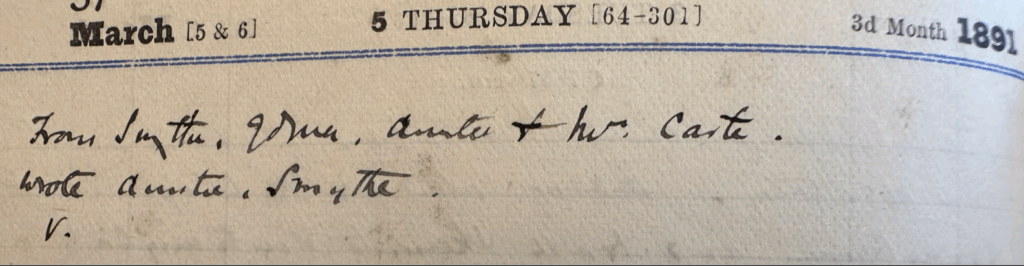

Here’s a beginner’s sample:

Now let’s suppose that we are doing research on Helen D’Oyly Carte. Here she is mentioned. After getting used to reading Sullivan, we now realize that on this date, Sullivan has received a letter from Helen. That doesn’t tell us much. Did she write often, or was this unusual? Is there something important in her letter, or was it purely social? Was something “big” going on, in Sullivan’s relationship with Helen?

To find out more, we’d like to find more diary entries mentioning Helen. But how? No one has ever transcribed Sullivan’s diaries into any form of searchable text. And we have more than 20 years of diary entries to check.

In a follow-up to this post, I’ll write about one person’s monumental work to help us. But first I will finish the story of Bertie’s Electrical Career and make my apology to Herbert. I wrote above that in 1892, he appears to have worked in Loughborough, and then, around November 1892, references to Loughborough in Sullivan’s diaries appear to end. I’m sure you can now understand my heavy use of the word appear. Since there is no way to search Sullivan’s diaries for keywords, the only way to positively know when a keyword has made its final appearance is to read every subsequent word of every subsequent day of every subsequent year.

For my story on Bertie’s career, I decided to scan Sullivan’s 1893 diary, looking for any mentions of Herbert, to get a feel for how Bertie’s activities and schedule might have changed from 1892. I wanted to find any references to his work, wherever that might be. And … I didn’t find any, until on 21 August, 1893 Sullivan wrote, from his summer home in Weybridge, “Bertie returned to work in City”. I might have taken that as a sign that Bertie still had a job, but if he did, it was no longer at Loughborough. (“The City” always refers to central London.) We know that eventually, Herbert obtained some position in The City as a … something to do with stocks. So when I finished scanning the 1893 diary, and found no more references to Loughborough, I assumed that most probably Bertie’s career with the Brush Electrical Engineering Company was over.

I’m sorry, Herbert

Then yesterday, I found myself scanning 1894, looking for something completely different, and on 25 January, saw this:

Called at Brush Company,

saw Sellon & found that Bertie had left the company, & not

a word to me! This [is] too bad.

Although Brush’s largest factory was in Loughborough, their head office was on Victoria Street in London, very close to Sullivan’s apartment. Sellon was probably R. P. Sellon, who was “Joint Manager” of the firm. So Bertie was working in the city, and working for Brush. The next day, Sullivan wrote:

Bertie came, & I talked seriously to him – but no talking – nothing

will ever give him stability or manhood.

Ouch!

There it was, confirmation that Herbert had worked for Brush, and evidence that he had done so through 1893. Reading these same diaries, Sullivan biographer Arthur Jacobs wrote, “From this period [1892] his nephew remained by his side as a household companion.” I pushed that date out to 1893, but it’s easy to see the basis for Jacobs’ conclusion. Now that I’ve pushed it out further to 1894, I guess we both owe Bertie a bit of an apology.

But the story isn’t quite finished. Again, I kept reading ahead; on 14 February, 1894, Sullivan wrote

Wire from Bertie “Brush

have offered clerkship cannot accept – must resign tomorrow, what

do you think”. wired back “cannot advise, send me full

details, can you make any temporary arrangement”.

Sullivan was in Monte Carlo. The next day he received a letter from his nephew, “recounting his sad experiences with Brush & Co:”. Sullivan “wired Bertie that his letter unsatisfactory, a clerkship not suitable to him & to consult Auntie before taking further steps.” Auntie is Fanny Ronalds.

Sullivan and Herbert exchanged more letters, but we aren’t told their contents. Sullivan returned to London in March. He was busy preparing for a concert of his works in Dublin, negotiating with Carte and Gilbert over revivals of their shows, arranging an elaborate party for his 52nd birthday, and of course betting on horses (his own horse Cranmer would run for the first time on 24 May). We don’t hear about Bertie’s travails again until 28 May:

Went to City – took Bertie to see

A. Rothschild & Carl Meyer.

To me, this sounds like yet another episode of What to do about Bertie?