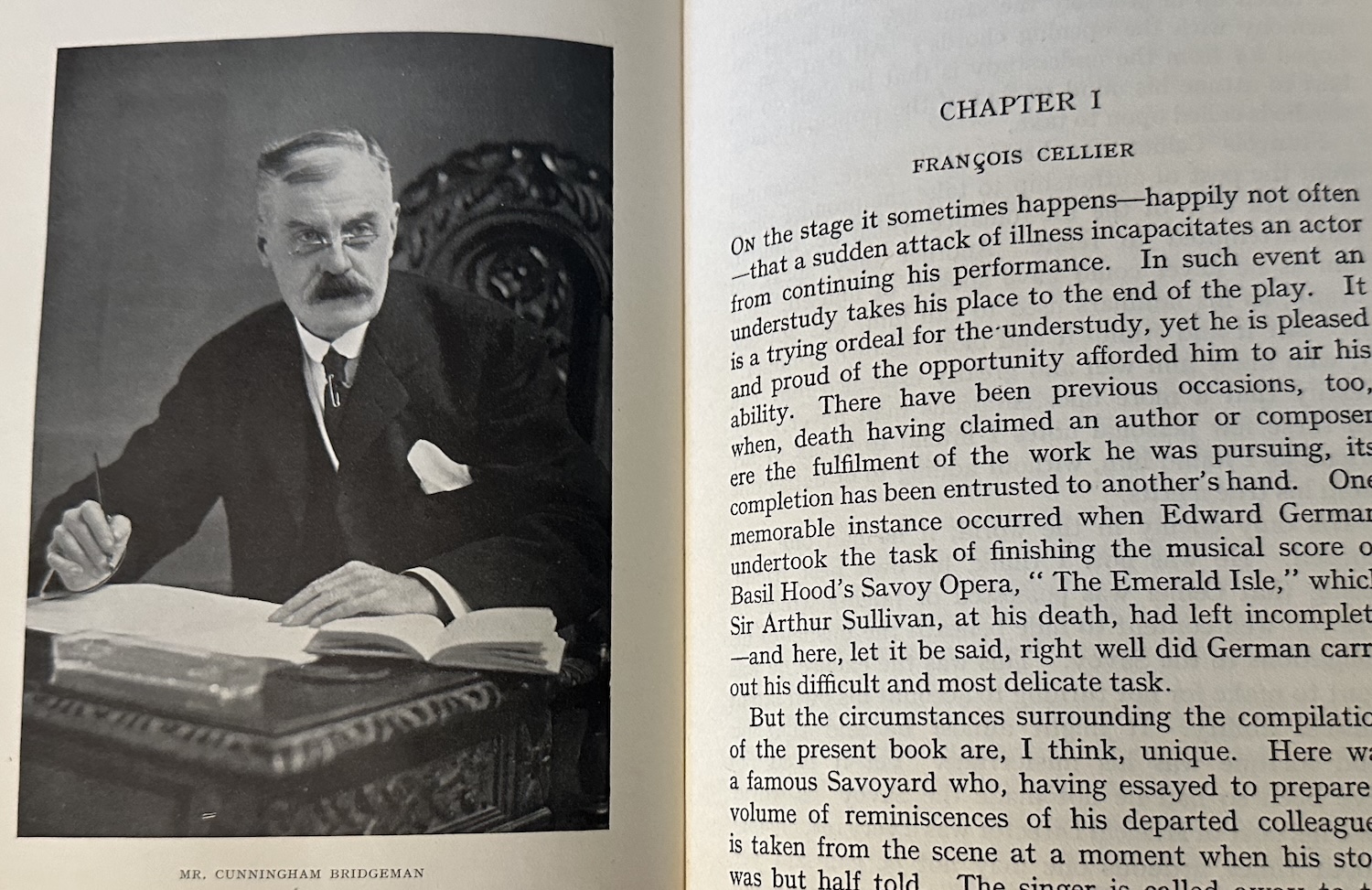

The short answer is, he was the coauthor of the early and influential book, Gilbert, Sullivan And D’Oyly Carte: Reminiscences Of The Savoy And The Savoyards (among other titles), written in 1913-1914 with François Cellier. That book, published with the imprimatur of Cellier—one of Sullivan’s closest friends and longest collaborators—is still today quoted by authors and Sullivan historians, often indirectly and unknowingly since some famous anecdotes from Sullivan’s life are first reported in Cellier and Cunningham’s book.

Despite bearing Cellier’s name on the cover, the book was largely the work of Cunningham Bridgeman. We know this because Bridgeman himself explains it. On page 164 (in my 1927, Second Edition copy), Bridgeman reports the death of Cellier, on 5 January 1914. At that point in their story, the authors had apparently written up to the 1884 revival of Gilbert & Sullivan’s The Sorcerer. After that, the remaining 258 pages are completely from Bridgeman. To his credit, Bridgeman delineates this change by labeling the section Part II and by Cunningham Bridgeman. There’s also the evidence of style. While Cellier’s portion of the book is not so over-written as Bridgeman’s, there are passages therein that match Bridgeman’s florid style.

So who is Cunningham Bridgeman?

In 1795, in Tavistock, Devon, there was born one Christopher Vickry Bridgman (d. 1876, with no “e” in his surname). He studied law and became a solicitor. He did a lot of work in bankruptcies, and became the Registrar for the county court district of Tavistock. He must have done well for himself. Two houses he owned still stand on the campus of Mount Kelly College in Tavistock—Hazeldon House (built for Bridgman), and Parkwood House (from his in-law’s family).

To the certain chagrin of genealogists and legal scholars, he named his first son Christopher Vickry Bridgman (1841–1909), sent him to law school, and soon had him made the Registrar for the county court district of Tavistock. In 1846 he named his second son Cunningham Vickry Bridgman (1846–1922). Sure, the first name was different, but now there were three Mr. C. V. Bridgmans living in the same small Devonshire town, and two of them were styled Esquire.

In January, 1901, just a few months after the death of Arthur Sullivan, Mr. Christopher Vickry Bridgman Junior, Esq., wrote an astounding letter to The Musical Times. Some of the anecdotes in Christopher Bridgman’s letter form the foundation of Sullivan creation stories:

It was in April, 1854, that Sullivan became a junior chorister, otherwise one of the fags, in the choir of the Chapel Royal, St. James’s. We numbered ten and were boarded and educated at the residence of the Master, the late Rev. Thomas Helmore, at 6, Cheyne Walk, Chelsea. Clad in our heavy scarlet and gold lace-adorned uniforms we used to walk twice each Sunday and Saint’s Day to St. James’s Palace, the total distance covered being ten miles. From the first, at the age of eleven, Sullivan furnished proof of much ability in educational subjects, and he had not been a chorister many months before he showed extraordinary talent, both in singing and composing. He was speedily promoted to the ranks of the four senior boys, and, subsequently, became principal soloist.

Among his schoolfellows were the brothers Cellier, Alfred (the gifted composer of “Dorothy”) and François, and Malsch (afterwards the distinguished oboe player), by all of whom he was much admired; but he was especially the chum and friend of myself, and we were close companions.

Keep in mind, for later, that Christopher Vickry Bridgman Junior, Esq., says of the young Arthur Sullivan, we were close companions. He tells of school vacations together:

My home was then at Tavistock, in Devonshire, and Sullivan’s at Sandhurst, where his father was Bandmaster at the Royal Military College. During the ‘parson’s fortnight’ the Christmas holidays I went to Sandhurst with Sullivan and he used to pass the summer vacation with me at Tavistock. He became much attached to my mother, herself a sweet singer and gifted musician. He used to pass many hours of his holiday time at the pianoforte, singing to her and playing her accompaniments.

I’m going to briefly interrupt Christopher’s narrative to note that this must have been the first time—though hardly the last time!—Arthur Sullivan spent some summer weeks at a stately country home. But of course the story packs an even bigger punch:

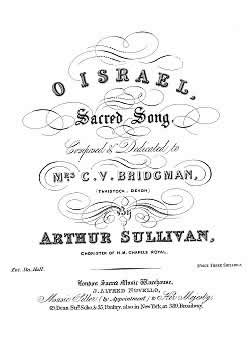

Thus it was, at the age of thirteen, his first published song (‘O Israel’) was composed while he was visiting my home. It was dedicated to my mother and published by Novello.

That sounds like a big claim, but we can examine the evidence. In large block letters on the cover of the Novello publication we see, “Dedicated to Mrs C. V. Bridgman.” If Parkwood House in Tavistock, Devin had anything, in 1855, it was C. V. Bridgmans. So, ok, perhaps the first published song by Sir Arthur Sullivan was composed in what is now a boy’s dormitory at the Mount Kelly School in Devon.

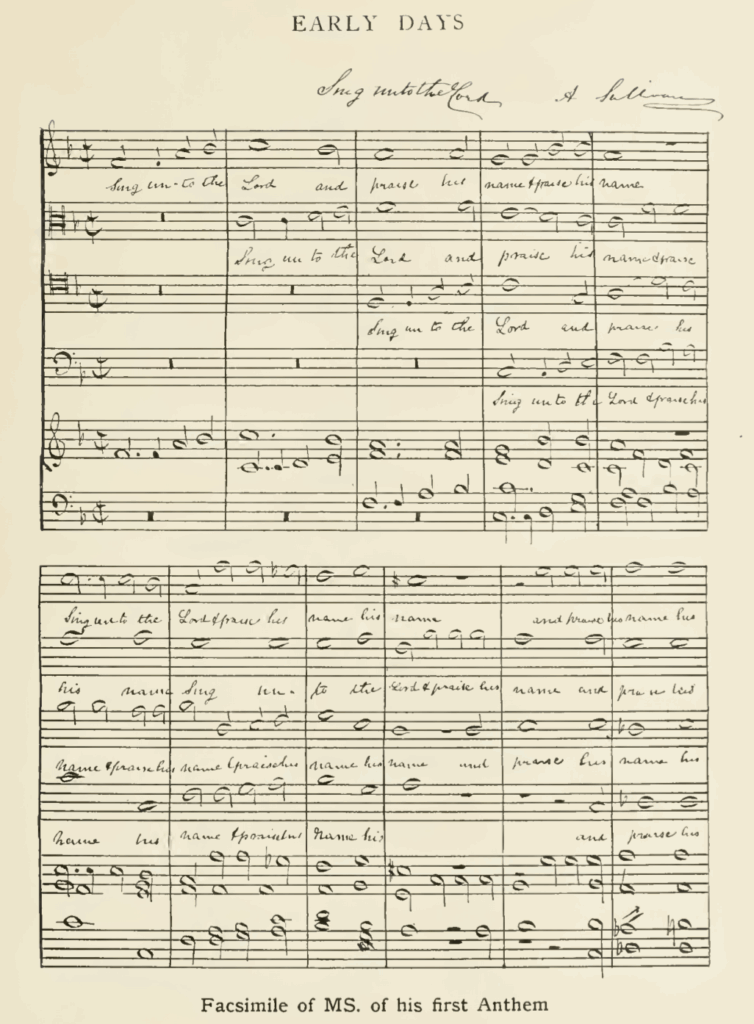

Christopher Vickry Bridgman Junior’s letter contains other anecdotes. He also recounts Sullivan writing another piece in 1855, the anthem Sing unto the Lord. Most Sullivan bios and Web pages describe this as unpublished and leave it at that. Herbert Sullivan—Arthur’s nephew—says it was sung at the Chapel Royal. Christopher Bridgman wrote that he had the manuscript in his possession in 1901, and that “when ‘The Gondoliers’ was being rehearsed at the Savoy Theatre” (that would have been in 1889), he (Christopher) showed the score to Sullivan, and “in the presence of W.S. Gilbert, Francois Cellier, D’Oyly Carte, and Jessie Bond, [Sullivan] acknowledged it as his first effort. Cellier took the manuscript to the pianoforte, and, running over the first few bars, he turned to Sullivan and said: “Why Sir Arthur, here is the refrain of ‘H.M.S. Pinafore!'”

The refrain of Pinafore? Erm … Quel F— are you talking about? (Am I the only one who prefers that expletive in the original Franglais?) I might excuse such nonsense from anyone without musical literacy, but this gentleman claims to be a former Chapel Royal Chorister. And for such an interesting story, no one else ever recounted it. (Pray correct me if I am wrong.) Sullivan records no such amazing happening in his diaries. The music resembles nothing from H.M.S. Pinafore, to my ears.

Worse for Bridgman’s claim, another book, Souvenir of Sir Arthur Sullivan, also published in 1901, says the score of Sing unto the Lord was given by Sullivan to his actual friend (I say actual here, because this friend is provably a long-time friend) William Hayman Cummings. Cummings even allowed the publishers to reproduce the first page of young Sullivan’s anthem.

But I am hardly the first to wince at some of Christopher Bridgman’s anecdotes. In the biography Arthur Sullivan A Victorian Musician, Arthur Jacobs debunks another Bridgman story:

On Sullivan’s death his fellow-chorister Bridgeman was to write in the Musical Times a memorial of those days. It is embellished with a highly circumstantial anecdote of a solo sung by Sullivan at the christening of Prince Leopold, Duke of Albany – and a comment made at rehearsal by Sir Michael Costa, who was conducting. The account, reproduced by various biographers, is unfortunately fictitious: Leopold was christened in June 1853, a year before Sullivan’s entry into the Chapel Royal, and on no other occasion at this period did Costa participate in such an event.

Of course we might kindly forgive a nice old gentleman getting some of his facts wrong when reminiscing about his long-passed school days. But in both of those anecdotes, he not only tells incredible stories, he recounts dialogue for them:

At the rehearsal, after having heard Sullivan sing the solo, Costa created much amusement among band and choir by saying to him: “Vell done Soolivan, very vell done. But you must put your accent as clear as your vords. Now, listen to me,” and then Sir Michael sang: “Sóofer léetle cheeldren to cúme after mé, and forbed them not, and forbéed them not, for of sooch is the kengdom of Háven.” So well did Sullivan sing on that Royal occasion that it pleased the Queen—whom we all so greatly mourn—to send him, through the Prince Consort, a special message of congratulation.

It is hard to see how one might forget they don’t have the score they say they have. Perhaps he had another Sullivan autograph score?

So who is Cunningham Bridgeman?

When Christopher Vickry Bridgman Junior was singing along with the future Sir Arthur Sullivan in London, Cunningham Bridgman was his 8-year-old brother, in Devon.

I had long assumed that Cunningham Bridgeman (he added the “e”) was an author, or a journalist—some sort of professional writer who could aid Cellier in producing a professional quality memoir. In 1900, Bridgman divorced, and in his court pleadings he said his occupation was Journalist. Ok, fair enough. What other books did he write? Or for which periodicals? Apart from a newspaper article written after the publication of his book, and a handful of letters to editors, I have found nothing. (Please update me, Dear Reader.)

So why did François Cellier choose Cunningham Bridgman as his coauthor?

Before I attempt to answer that question, I can’t resist dishing out more details of his juicy divorce story. Bridgman was the plaintiff in that case. He was married to an actress with the stage name Christine Valmer. Her real name was Johanna Bertha Hunwick. Edward Hunwick was her first husband; at age 24, Johanna was a widow. Her name at birth was Johanna Martha Bertha Nitschke. Johanna married Cunningham in 1889 and they were together until September 1900, after she checked into a London hotel for a week with a Mr. Alexander Gordon Ross, the grandson of Sir Alexander Cornewall Duff-Gordon, 3rd Baronet. The jury found in Bridgman’s favor, and awarded him £500 damages, from Ross. That’s around £78,000 today. Johanna’s version of events was of course different. She said … well, never mind.

Why did François Cellier choose Cunningham Bridgman as his coauthor? And why should we consider Bridgeman an expert on Gilbert & Sullivan?

All in good time! But first, a rather exciting discovery at the Library of Congress …

[…] In Part 1 of this story I began to explore the mystery of Cunningham Bridgeman. The mystery is, who is he, and how did he come to coauthor, with Sullivan collaborator Frank Cellier, an early and influential book about Gilbert & Sullivan? So far, we’ve seen that in 1855, when the young Arthur Sullivan was singing in the choir of the Chapel Royal in London, one of his fellows there was a lad called Christopher V. Bridgman. Cunningham V. Bridgman was Christopher’s 8-year-old little brother, who was then still living at their family home in Devon. […]