As we set forth in Part 1 of this series, Cunningham Bridgeman was the coauthor, with François Cellier, of the book Gilbert, Sullivan And D’Oyly Carte: Reminiscences Of The Savoy And The Savoyards. This was an early and influential memoir of the careers of Gilbert and Sullivan, written by a well-known Savoy Theatre insider—François Cellier—and a … well, who was Cunningham Bridgeman?

In the book, Bridgeman claims to have had a “close intimacy” with Arthur Sullivan, and to have known Sullivan “long before he met the future partner of his fame, Sir William Gilbert”. The latter claim is literally true, if misleading. Bridgeman met Sullivan at Bridgeman’s parents’ home in Devon, when Sullivan came to stay with his school friend, Christopher Bridgman, Cunningham’s older brother. Cunningham was about eight years old at the time. But what evidence can we find for Bridgeman’s claim of a “close intimacy” with Sullivan, after age eight? No Sullivan biographies mentioned Bridgeman until after the 1914 publication of Bridgeman’s book. Later authors copy anecdotes from Bridgeman’s book, but provide no evidence of any Bridgeman relationship with Sullivan.

Bridgeman is not mentioned in Savoy star Rutland Barrington’s memoir Rutland Barrington: A Record of Thirty-five Years’ Experience on the English Stage (1908), except to note that the drawing on the book’s cover is by “Mr C.V. Bridgman”. That book’s lack of reference to Cunningham Bridgeman is notable, as we shall see in Part 3.

In Gilbert and Sullivan: A Dual Biography, Michael Ainger confuses Cunningham with his brother Christopher, falling into a trap I have visited myself! On page 11 of Cellier and Bridgeman’s book, in the section nominally attributed to Cellier, we read:

During [Sullivan’s] school-boy days at St. James’s Chapel Royal—to be precise, it was in his thirteenth year, 1855—his first composition was accepted and published by Novello. This was a sacred song entitled, “O Israel.” It was written during a holiday spent in Devonshire at the home of a schoolchum and fellow-chorister. As shown on its title-page, this embryo composition was “dedicated to Mrs. Bridgeman of Parkwood, Devon,” the mother of Sullivan’s school-fellow.

With no further details given, can we blame a reader for assuming that Cunningham Bridgeman was himself that “schoolchum and fellow-chorister”? But in reality, François Cellier, his older brother Alfred, Arthur Sullivan, and Christopher Bridgman were all boys at the Chapel Royal. Cunningham never was.

What does Sullivan write about Bridgeman?

To the best of my knowledge, Sullivan’s diaries (which do not begin in earnest until 1881) make no mention of Bridgeman. As always with the diaries, remember there is no way to search them, but I have read no entry involving Bridgeman. Neither the name Bridgman nor Bridgeman appears in Dixon’s Index. In the cases where Bridgeman relates a Sullivan anecdote in his book, where I can determine an approximate date for the anecdote, I have tried to find a reference to Bridgeman in a diary entry near that date. I’ve had no luck.

What does Bridgeman write about Bridgeman?

Quite a lot, but he does not provide many anecdotes in which he claims to be in Sullivan’s presence. Where he does, the stories can sound bizarre. Again quoting Bridgeman’s book:

Being a very old friend of Sullivan’s, I was privileged to lunch with him on Sundays. This was more particularly during a period when his mother was ‘keeping house’ for him in Victoria Street, Westminster. On one occasion […] I was, as usual, heartily welcomed by Mrs. Sullivan […]

That detail sets the “period” of this story in the 1870s. Mrs. Sullivan moved to Fulham after the death of Fred Sullivan in 1877. Continuing the story:

The moment Sullivan arrived and saw that I was present, without waiting even to remove his overcoat, he went straight to the piano, saying, ‘What do you think of this for a tune, Bridgeman?’ To my amazement I recognized the refrain of a very unacademical ditty called ‘Impecuniosity’ which, a year or two ago, I had perpetrated […] ‘Well, old friend,’ [said Sullivan], ‘don’t be surprised or angry if you hear something very like it in my next opera.’

Bridgeman goes on to say Sullivan’s next opera was The Mikado. The Mikado premiered in 1885, three years after the death of Sullivan’s mother. Confused? I certainly am.

In other stories, Bridgeman describes events at which the reader might readily assume both he and Sullivan were present, but he does not explicitly state that either of them were there. In one example he describes a Savoy Theatre company dinner held in London on 13 March, 1887. Sullivan’s diary for that day reads “Left Monte Carlo at 11.33”. (He was on his way to Paris.)

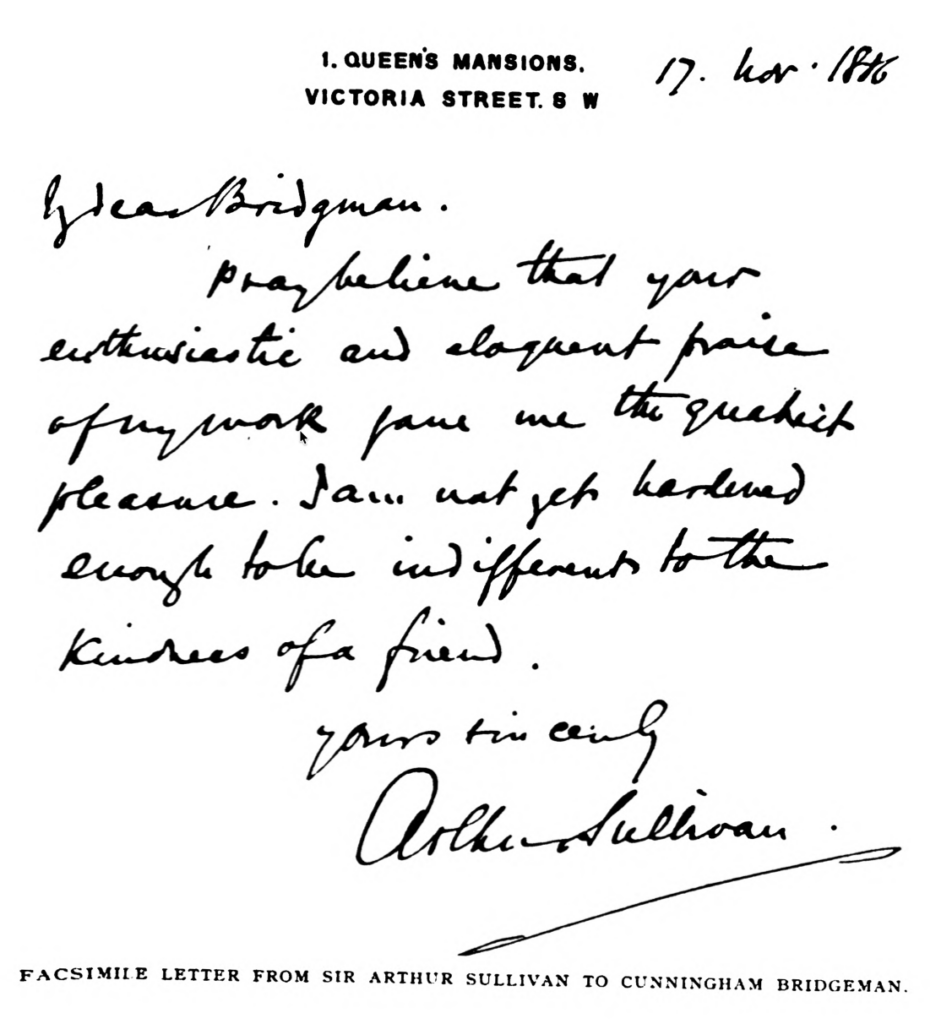

Perhaps as evidence of his “close intimacy” with Arthur Sullivan, Cunningham includes a letter he received. Dated 17 November, 1886, the letter reads [the transcription is my own]:

My dear Bridgman,

Pray believe that your enthusiastic and eloquent praise of my work gave me the greatest pleasure. I am not yet hardened enough to be indifferent to the kindness of a friend.

Yours sincerely

Arthur Sullivan

I have read many letters from Sullivan. To me, this sounds like a polite response to a fan who has either sent Sullivan some praise in a letter, or written a positive article about Sullivan for a periodical.

If we cannot establish a relationship between Bridgeman and Sullivan from Sullivan biographies, Sullivan’s diaries, or even Bridgeman’s own writing, might we find evidence of it in the press? To find out, I return to my original question, Who Was Cunningham Bridgeman?, and see if I can write the Bridgeman biography that no one has ever attempted. It’s actually more interesting than I imagined.