I know of no book or website that outlines the life of Cunningham Bridgeman, so this narrative is based on public records and newspaper reports. Why am I interested in his life? We saw in Part 2 that Bridgeman claims to have had a “close intimacy” with Arthur Sullivan. And he wrote a popular account of the work and life of Gilbert & Sullivan. How much credence may I place in Bridgeman’s stories? As it happens, whatever answer I may arrive at, Cunningham Bridgeman led an interesting life. He is sort of a Forest Gump.

As I mentioned in Part 1 of this series, Cunningham Vickry Bridgman (without the “e” he later added to his surname) was born in December, 1846, in Tavistock, Devon. For Sherlock Holmes fans, that is the same Tavistock, just west of Dartmoor, mentioned in The Adventure of Silver Blaze (known for the “curious incident of the dog in the night-time”). When Cunningham was eight, his older brother Christopher Vickry Bridgman (Junior) brought home a thirteen year old Arthur Sullivan from Thomas Helmore‘s school in London, for a summer break visit. Apart from that meeting, I have yet to confirm any moment when Sullivan and Cunningham were ever together, outside of public performances. But my research is ongoing.

Like his father, Christopher Jr would study law, become a solicitor, and later be the Registrar of the county court district of Tavistock. Unlike Christopher, Cunningham was not sent to London for his primary school education. In interviews, Bridgeman said he attended The College School in Gloucester, one of the oldest schools in Britain. Today it is called The King’s School, Gloucester. In 1890 Frederick Hannam-Clark published a book called Memories of the College school, Gloucester, during 1859-1867. Sadly for Bridgeman, and us, he isn’t mentioned therein. That’s all I know of Bridgeman’s first 13 years.

By the census of 1861, his father had moved the family, and his legal practice, to Plymouth. Cunningham was not with them. Cunningham was onboard the training ship H.M.S. Britannia in Portsmouth harbor, where he was a Naval Cadet. A Cadet was the lowest rank in the officer class. In 1860, when Bridgeman signed up at age 13, cadets were the sons of the gentry and the rich, although admission into the service was not guaranteed. Prospective boys first had to pass written examinations. Although, as Admiral Lord Charles Beresford later remembered, “the qualifying examination was not very formidable in those easy days,” it did include “a little English, less French or Latin (with the ‘aid of a dictionary’), a ‘satisfactory knowledge of the leading facts of Scripture and English History,’ a certain amount of geography, and an elementary knowledge of arithmetic, algebra and Euclid.” These were educated boys. Onboard their ships, they had servants.

After passing his exams in September, 1860, Cunningham was billeted to H.M.S. Britannia for his sea training. On 24 September, Charles Dickens wrote a short account of his own visit to the Britannia in a letter. He wasn’t there to see Cunningham Bridgman, but rather his own son, Sydney Smith Haldimand Dickens. As new cadets were examined and accepted in batches, Dickens and Bridgman were likely qualified at the same time. By age 13, Bridgeman has met Arthur Sullivan and Charles Dickens.

Get used to this sort of coincidence.

Bridgeman and Dickens trained as cadets on H.M.S. Britannia until early December, 1861. During those 15 months, across the Atlantic, Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated as president, 13 states declared themselves separated from the United States, the first battles of the American Civil War were fought. On the seas, Lincoln initiated a blockade of southern ports, hoping to deprive the Confederacy of the enormous profits that came from selling cotton abroad. At that time, England was the world’s high-tech capital for manufacturing cotton cloth. Any interruption in the importation of raw cotton from the States could bankrupt mill owners and make redundant thousands of mill workers.

Knowing (or at least fearing) that the Confederacy could not win a war with the North without some help, Confederate leaders sought to use their cotton leverage to convince Britain to grant the CSA full diplomatic recognition, make trade agreements, and perhaps enter the war on their side. They dispatched two envoys to Cuba where they boarded a British mail steamer, the Trent. On 8 November, 1861, the ship was intercepted by a US warship whose captain searched the Trent and took the Confederates prisoner.

The British strongly protested this action as illegal and a violation of their neutrality. They demanded the release of the captive Confederate envoys. While officially remaining neutral during the war, Britain had its own territories to protect, in Canada and in the Caribbean. Just one month after “The Trent Affair,” Britain began sending ships and soldiers across the Atlantic.

One of those ships was H.M.S. Orlando. On 24 December, 1861, Bridgeman and Dickens found themselves aboard her, bound for Halifax, Nova Scotia. It was not a pleasant voyage. The Orlando was one of the longest wooden warships ever constructed, 336 feet in length. It was a steam “screw” frigate capable of speeds of 12-13 knots. In the first five days of the voyage, the seas were calm and the ship sailed half the distance to Halifax. “But then, alas, troubles came thick, fast, and heavy”, wrote the Birmingham Daily Post on 8 February, 1862. Gales blew up. Bits of the ship started to be blown off. But worse was that a 300-foot wooden ship doesn’t sail well in high seas. (Picture a long ship maneuvering between two large swells, and you can imagine the great stresses on its hull.) The ship leaked, badly. The water below decks rose high enough to put out some of the fires in the boilers. Bilge pumps failed. Higher decks leaked as well. “Over the beds of officers it was necessary to have the protection of awnings.” For two days the ship’s very seaworthiness was in question. The gales continued. It was another 14 days before land was sighted.

The ship spent several weeks being repaired at Halifax before it sailed on to Bermuda. Another letter from Dickens tells us his son was there in April, 1862. By then, both of the lads had received their first promotions, to Midshipman. In his book, Bridgeman recounts a story of a “coloured” lady in Bermuda named Dinah, who sold “tuck” on board the Orlando. In Bridgeman’s telling, Dinah was fond of Sydney Dickens and invited him to tea at her home on shore, and Cunningham, as Dickens’s “particular chum,” was invited to come along.

That story would not pique my interest if I had not read Charles Dickens’s letter of 24 September, 1860:

At the Waterloo station we were saluted with “Hallo! here’s Dickens!” from divers naval cadets, and Sir Richard Bromley introduced himself to me, who had his cadet son with him, a friend of Sydney’s. We went down together, and the boys were in the closest alliance. Bromley being Accountant-General of the Navy, and having influence on board, got their hammocks changed so that they would be serving side by side, at which they were greatly pleased.

In the same book in which Bridgeman claims a special relationship with Arthur Sullivan …

Well, to be fair, Dickens also records that his son was very popular among all the boys. And Sir Richard Bromley‘s name will soon turn up again.

Bridgeman could not have stayed long in Bermuda, because on 24 May he was transferred to H.M.S. Royal Adelaide. The Adelaide was the flagship of the Admiral of Devonport (Plymouth, England). It was used as a depot and temporary billet for naval “supernumeraries”—men awaiting new assignments. Bridgeman was back home. There is an unexplained gap in his service record, from 22 June 1862 through to 25 December, but on Christmas he is assigned to H.M.S. Meeanee. He probably spent the next six months cruising around the Mediterranean, where he saw no action, but made stops at Gibraltar, Malta, and Naples. (A fun fact about the Meeanee: her Captain, George Wodehouse, was a quite distant cousin of later author P.G. Wodehouse.)

In 1863, something happens to Bridgeman, but I don’t know what. On 26 June he is back on H.M.S. Royal Adelaide, and is granted six weeks leave, with pay. That is the end of his naval service record. I haven’t found any reports of injuries onboard H.M.S. Meeanee, but in his book, Bridgeman says he was, at some time which he doesn’t specify, “confined to bed for nearly a year in the Royal Naval Hospital, Plymouth, through an accident contracted in the service.” During this time, he says, he wrote a play.

From August 1863 through to January 1869, the trail of Cunningham Bridgeman goes dark.

During this time, Frederick Clay writes the music for W.S. Gilbert‘s Ages Ago while working at the Treasury, Wilfred Bendall studied at the Conservatory in Leipzig (Sullivan’s alma mater) and started to write songs while working as a clerk, George Rutland Fleet attends the prestigious Merchant Taylors School and then later works … as a clerk. I have no idea why I thought to mention these three gentlemen just now.

By March 1869, Bridgeman is living in London. He has a new job. He is a Booking Clerk at the London Bridge Station of the London, Brighton, and South Coast Railway. Their employee ledger notes that Bridgeman was recommended by “Mr Lopes, Director.” This is an outstanding reference, probably facilitated by his father. “Mr Lopes” was probably Sir Massey Lopes, Privy Council, MP for Devonshire South and director of The Great Western Railway, a position he will hold for forty years. Lopes and Christopher Bridgman Sr had done some land deals in Devon, and probably had other connections (Lopes’s younger brother Ralph was a prominent barrister).

Cunningham’s living quarters are likewise the result of happy connections. In the census of 1871, Bridgeman is living in Winchester Street in London’s Pimlico district. It hasn’t changed much; only then all those white stucco terraced houses were newer. But it is not Cunningham’s house. He and his younger brother Frederick are “boarders” at the home of James C. Martin. Mr. Martin is also a Portsmouth man, now working as a clerk for the Accountant-General of the Navy, a department headed by—I’m sure you remember—Sir Richard Bromley, the father of Bridgeman’s fellow cadet from H.M.S. Orlando and chum of Sydney Dickens: Arthur Bromley. James C. Martin will work at the Admiralty for over thirty years.

Cunningham Bridgeman will work for the railway company for several years. But he had other ambitions.

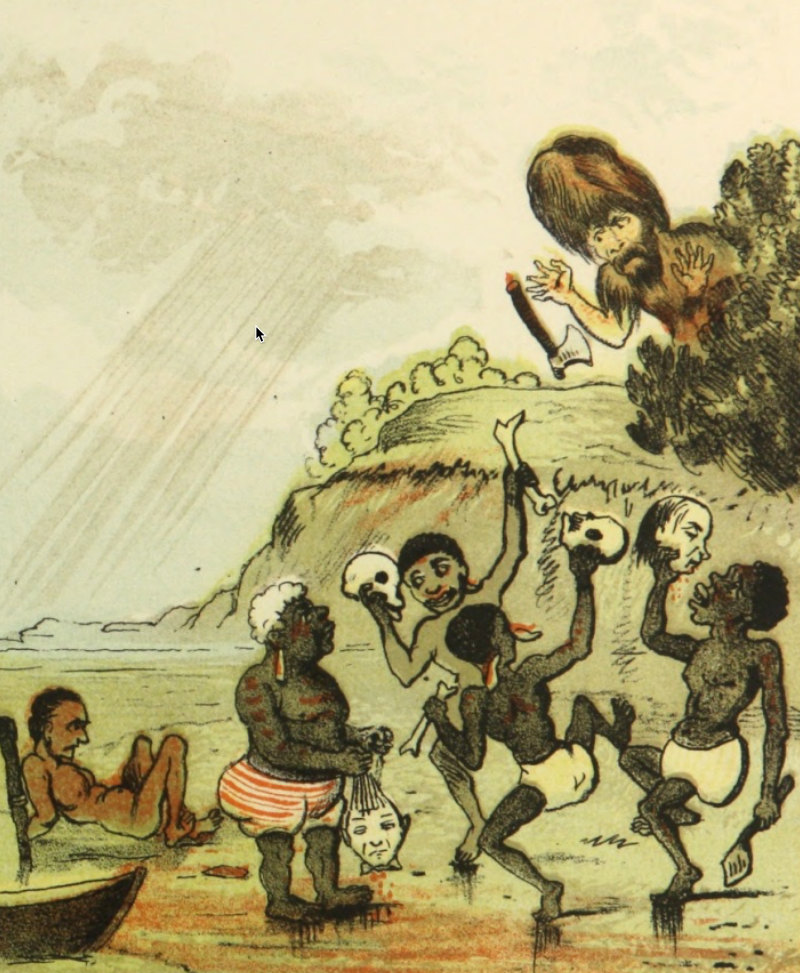

Dean & Son was a London publishing firm that pioneered “toy books” for children. Around 1870 they produced Ridiculous Robinson Crusoe, which you may read here. The book begins with a young lad who dreams of going to sea, but his father objects. He nonetheless sails off on a ship, where other boys torture him and play practical jokes. Their voyage is very smooth for some days:

But at length, alas! the wind shifted,

And quickly increased to a gale;

Masts fell on the deck, we then drifted,—

All the horrors I need not detail.This will not be the last time Cunningham Bridgeman uses his youthful maritime remembrances in his work. His career is about to pivot.